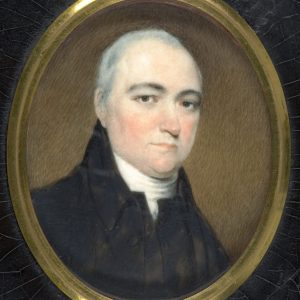

Timothy Dwight:

The Freeing of a Reputation

According to the report published in 2001, “Yale, Slavery and Abolition,” nine of the Yale’s twelve residential colleges are named for men who either owned slaves or gave public support to slavery. Among the accused stands Timothy Dwight the elder (President of Yale 1795-1817), for whom both Timothy Dwight College and Dwight Hall are partly named.1

In the fall of 2001, in the wake of the slavery report’s allegations, Dwight Hall considered a name change, but then in a compromise move, installed a plaque in their building which proclaims:

“With this plaque Dwight Hall at Yale renounces the pro-slavery thought and actions of Timothy Dwight, while reaffirming our predecessors’ work on behalf of justice and equality.”

The plaque has its origin in sound intentions, but patently slipshod scholarship. Dwight plainly denounced slavery. He statedly anticipated its abolition, while describing abolition as less than justice required.

Who is being condemned?

Let’s pause for a little historical context. Timothy Dwight is the man most responsible for Yale’s transformation from a small regional college to a major national university. Not only an exceptional college president, he was a man of God with a mighty concern for students. When Yale departed from her historic foundation and embraced a fashionable rationalism and atheism, it was Dwight’s praying, preaching and intellectual challenge to the new philosophy that broke its hold on the student body. Spiritual revival visited the campus no fewer than four times in Dwight’s tenure, and many of the college’s future professors and presidents were brought to repentance and faith during these and subsequent revivals.

When a spiritual awakening in 1878-79 sparked the founding of a chapter of the Young Men’s Christian Association at Yale in the 1880s, it seemed natural to name first the chapter’s building and then the association itself after Timothy Dwight. There was no brighter light in Yale’s history than the elder Dwight, and no better example of sacrifice and service for Christ.2

The report’s case against Dwight

Dwight Hall’s hasty move to dissociate from President Dwight is not too surprising given that they no longer hold the faith he professed. But the speed of their action also suggests a fear of commemorating an unfashionable hero and scant knowledge of the thought and action of their predecessor. For Dwight’s legacy on the question of slavery is simply not as “Yale, Slavery and Abolition” represents it. Not even close.

The report purports to review Yale’s relationship to slavery and concludes that the school was founded and supported on money made from slave labor, was a significant source of pro-slavery thought, and produced a considerable number of pro-slavery graduates. Yale’s antebellum faculty, according to the report, were at best tepidly antislavery, and at worst actively pro-slavery.3

Timothy Dwight is in many ways critical to the report’s argument about Yale’s involvement with slavery, for it credits him with fostering pro-slavery attitudes in his students and influencing the college climate on this subject long after his death.

A review of the report’s charges against him will fairly test the report’s own validity.

A look at the record: “Yale, Slavery and Abolition”

Fallacy #1: Dwight helped sell Jonathan Edwards’s slaves.

Fallacy #1: Dwight helped sell Jonathan Edwards’s slaves.

Minor errors pepper the slavery report, and some of them are chronological. For instance, two separate pages record that Timothy Dwight the younger became president of Yale in 1881, when in fact he became president in 1886. Leonard Bacon is said to have graduated from Yale in 1783. That would have been a remarkable feat: Bacon wasn’t born until 1802.4

But the writers of the slavery report commit a major chronological blunder when they have Timothy Dwight, in administering the wills of his grandfather and grandmother Jonathan and Sarah Edwards, participate in the sale of their slaves. The fact is that in August 1759, when those wills were executed, our Timothy would have had to be one very precocious seven-year-old to be executing wills or selling slaves.

While the error is most explicit in the online version of the report, neither the online version nor the printed text differentiate in this instance between President Timothy Dwight, born 1752, and his father of the same name, born 1726.5 It is Dwight’s father who is most likely the “Timothy Dwight, Jr.” of the executor’s report.6

A look at the record: “Yale, Slavery and Abolition”

Fallacy #2: Dwight excused the slave trade and had contempt for African Americans.

Fallacy #2: Dwight excused the slave trade and had contempt for African Americans.

In 1810, the daughters of three prominent New Haven citizens decided to begin a school to teach black girls to read. President Dwight preached a sermon in support of this and other charitable projects,7 but singled this one out as most interesting to him personally. Despite his obvious purpose to promote the school, the writers of the slavery report select a quote from his sermon to demonstrate that Dwight was in fact using the occasion to make excuses for the slave trade.8 Regarding New Haven’s blacks, Dwight is quoted as follows:

“Our parents and ancestors have brought their parents, or ancestors, in the course of a most iniquitous traffic, from their native country; and made them slaves. I have no doubt, that those, who were concerned in this infamous commerce, imagined themselves justified; and I am not disposed to load their memory either with imprecations or censures.”9

“Yale, Slavery and Abolition” doesn’t give Dr. Dwight a chance to say what he is disposed to do, but we should. Starting a couple lines above the quote, here is a transcript of what Dwight actually said (emphasis his):

“Among these [charity] schools, I confess, that I feel a peculiar interest in that, which has been established for the benefit of the female children of the blacks. This unfortunate race of people are in a situation, which peculiarly demands the efforts of charity, and demands them from us. Our parents and ancestors have brought their parents, or ancestors, in the course of a most iniquitous traffic, from their native country; and made them slaves. I have no doubt, that those, who were concerned in this infamous commerce, imagined themselves justified; and am not disposed to load their memory either with imprecations or censures. Happily for us, the question has been made a subject of thought and investigation. This decided it at once; and we are now astonished, that it could ever have given rise to a single doubt. Under the influence of overwhelming conviction, we have made the descendants of these abused people free.”10

Dwight is here speaking of New England’s emancipation of slaves (see page 13), and he makes his position clear. The enslavement of Africans was patently wrong, his generation has seen it clearly and has set about freeing slaves. But this, he says, isn’t doing enough:

“Here we have stopped; and complimented, and congratulated, ourselves for having done our duty. But not withstanding this self-complacency, it is questionable, my Brethren, whether we have rendered to the present race of this people any real service.”11

Though the writers of the slavery report insist that Dwight felt contempt for African-Americans, in this sermon he unequivocally states that they are not “weaker, or worse, by nature” than others, but have been put at a disadvantage by the sin committed against them. Enslavement has established the conditions that make for “sloth, prodigality, poverty, ignorance and vice” in the black community. It is up to the children of the enslavers to give to the children of the enslaved “knowledge, industry, economy, good habits, moral and religious instruction, and all the means of eternal life.”

Dwight is soberly convinced that slavery is a multi-faceted evil that requires definite redress, and unlike many antislavery men of his time, or even later, he was willing to deal with the social situation it had created:

“It is in vain to alledge, that our ancestors brought them hither, and not we. . . . We inherit our ample patrimony with all its incumbrances; and are bound to pay the debts of our ancestors. This debt, particularly, we are bound to discharge: and, when the righteous Judge of the Universe comes to reckon with his servants, he will rigidly exact the payment at our hands. To give them liberty, and stop here, is to entail upon them a curse.”13

In short, if Dugdale, Fueser and Alves, the authors of the slavery report, had not branded Timothy Dwight a pro-slaver, they might more sensibly have used him as poster boy for a Connecticut campaign for reparations for slavery. Did they actually read The Charitable Blessed? It is known that by lecturing Dwight “raised a considerable fund” for the African American school, and that the work continued for a number of years.14

A look at the record: “Yale, Slavery and Abolition”

Fallacy #3: Dwight defended slavery in the United States, but condemned European and West Indian slavery.

Fallacy #3: Dwight defended slavery in the United States, but condemned European and West Indian slavery.

That Dwight was against the perpetuation of slavery in the United States is clear: as we have already seen, he didn’t think mere liberation of the slaves enough. That he looked forward to the end of slavery from as early as 1798 we know from his sermon The Duty of Americans, at the Present Crisis . . . , where, in listing recent works of God he notes:

“Measures have, in Europe, and in America, been adopted, and are still enlarging, for putting an end to the African slavery, which will within a moderate period bring it to an end.”15

Though Dwight may have guessed wrong about how soon slavery would end in America, he looked on its approaching demise with thankfulness. The authors of the slavery report appear to be unaware of what Dwight said in both The Charitable Blessed and The Duty of Americans . . . when they accuse him of hating slavery as it was in other parts of the world, but rejoicing in that practiced in America.16 They rest this claim on some lines from Greenfield Hill, a poem Dwight published in 1794. In a description of Connecticut village life, Dwight includes a view of the conditions of slavery:

“But hark! what voice so gaily fills the wind?

Of care oblivious, whose that laughing mind?

‘Tis yon poor black, who ceases now his song,

And whistling, drives the cumbrous wain along.

He never, dragg’d, with groans, the galling chain;

Nor hung, suspended, on th’ infernal crane . . .

But kindly fed, and clad, and treated, he

Slides on, thro’ life, with more than common glee . . .

Here law, from vengeful rage, the slave defends,

And here the gospel peace on earth extends.

He toils, ‘tis true; but shares his master’s toil;

With him, he feeds the herd, and trims the soil,

Helps to sustain the house, with clothes, and food,

And takes his portion of the common good:

Lost liberty his sole, peculiar ill,

And fix’d submission to another’s will.”17

Taken in isolation from the rest of the poem, this passage can be read as a portrait of jolly slavery in ye olde Connecticut. In context, though, it is a comment on the lack of brutality in that slavery. In Connecticut, the law and the Gospel keep the slave from the terrible experience of slaves elsewhere. Some lines not quoted from the above passage note what the New England slave does not have:

“No dim, white spots deform his face, or hand,

Memorials hellish of the marking brand!

No seams of pincers, fears of scalding oil . . . .”18

Dwight moves from this on to condemnation of slavery as a whole. It is a destroyer, wherever it exists. Picking up from the last lines quoted in the slavery report:

“Lost liberty his sole, peculiar ill,

And fix’d submission to another’s will.

Ill, ah, how great! without that cheering sun,

The world is chang’d to one wide, frigid zone;

The mind, a chill’d exotic, cannot grow,

Nor leaf with vigour, nor with promise blow.”19

Dwight says a young slave starts out “[f]irm [in] frame, and vigorous [in] mind”, but slowly the consciousness and reality of bondage begins to crush him. Slavery degrades him: he is “[c]ondition’d as a brute, tho’ form’d a man.” Dwight proposes satirically that future sages, looking at Africans, will ask “why two-legg’d brutes were made by HEAVEN” when in fact heaven didn’t make them at all, but slavery did. Slavery destroys its victims intellectually, morally, and spiritually. Here is Dwight’s fierce indictment of it:

“O thou chief curse, since curses here began;

First guilt, first woe, first infamy of man;

Thou spot of hell, deep smirch’d on human kind,

The uncur’d gangrene of the reasoning mind;

Alike in church, in state, and houshold all.”20

Please note that Dwight regards slavery as gangrene on an otherwise “reasoning mind,” and equally bad in church, state, and household. Unquestionably, Dwight here condemns slavery in Connecticut, for no other place has yet been mentioned in this part of the poem. Before he here turns to European or West Indian slavery, Dwight notes that slavery has reigned in all earth’s ages “[a]nd all her climes, and realms, to either pole,” but it is everywhere man’s defeat and “Satan’s triumph.” The slavery report’s interpretation of Greenfield Hill is based on a failure to actually read the poem. In his notes to the poem, Dwight says “Some interesting and respectable efforts have been made, in Connecticut, and others are now making, for the purpose of freeing the Negroes.”21

A look at the record: “Yale, Slavery and Abolition”

Fallacy #4: Dwight defended Southern slaveholding.

Fallacy #4: Dwight defended Southern slaveholding.

In 1815, an anonymous Englishman’s review of life in the United States roused Dwight to offer a corrective response. Among other things, Dwight was offended that the unknown writer criticized slavery and the slave trade of the American South, but ignored British participation in the same. Dwight’s object in replying to this part of the attack, he explains, is not to defend the slave trade or poor treatment of slaves, but simply to ask that these terrible things not be made “a characteristical disgrace peculiar to [America].”22 Slavery in the British dominions should be acknowledged, too. Beyond that, he gives the British writer permission to “stigmatize both” American and British slaveholders as severely as he pleases.23 Dwight goes on to commend British efforts to end slavery.

“Yale, Slavery and Abolition” draws out a footnote from Dwight’s text to demonstrate his supposed support for the Southern slaveholder:24

“The Southern Planter, who receives slaves from his parents by inheritance, certainly deserves no censure for holding them. He has no agency in procuring them: and the law does not permit him to set them free. If he treats them with humanity, and faithfully endeavors to Christianize them, he fulfills his duty, so long as his present situation continues.”

In context Dwight is plainly not cheering for Southern slaveholding or Southern slavery. He anticipated that slavery in England and America would be ended by government-sponsored abolition. Manumission laws in the South had been progressively tightening from the late 1790s forward. It had become increasingly difficult for a Southerner to free his slaves. Freed slaves were often kidnapped and reenslaved. Various subterfuges were necessary to secure the liberty and well-being of many former slaves, and as a law-abiding man Dwight may have objected to these.26 The Southern inheritor of slaves might hold them just “so long as his present situation continues,” and as we have seen, Dwight thought that it could not continue much longer. In the notes to Greenfield Hill, Dwight says “The manners of Virginia and South Carolina cannot be easily continued, without the continuance of the Negro slavery; an event, which can scarcely be expected.”27

A look at the record: “Yale, Slavery and Abolition”

Fallacy #5: Timothy Dwight was a slaveholder himself.

Fallacy #5: Timothy Dwight was a slaveholder himself.

Here we confront an especially tawdry allegation. On the basis of a manuscript found in the Dwight papers at Yale, the slavery report concludes that in 1788 Timothy Dwight purchased a female slave named Naomi. However, in the manuscript, which is Dwight’s covenant with Naomi, he flatly states “I never intended her for a slave.” Naomi is asked to work for Dwight and his family only until she refunds the money he paid for her and will pay for her clothing. The agreement specifically calls the seven pounds, sixteen shillings that Naomi is to refund to Dwight per year a “rate of hire,” something Dwight need not have given to one he bought and planned to hold in slavery.28

Robert Forbes, associate director of Yale’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, states that instead of buying himself a slave, Dwight is here buying a slave in order to free her.29 It is likely that a deed of mercy is being mistakenly judged a crime.

More clear and convincing evidence

The slavery report neglects other evidence about Dwight and slavery. The first antislavery society in Connecticut was formed in 1790, and Dwight joined it, signing a copy of its 1792 constitution (see page 11). Surviving correspondence shows that he was second in line to preach at the group’s September 1794 meeting.30 Green’s Register for the State of Connecticut for 1792 also records Dwight’s membership in the society.31

Made up in large part of Yale men, the society in 1792 petitioned the state legislature for the total abolition of slavery, and a bill freeing all slaves by April 1, 1795 indeed passed the lower house, though the Council later rejected it. “Yale, Slavery and Abolition” portrays the antislavery group as too weak-kneed to actually work for abolition in Connecticut, and Dwight’s connection with it is not mentioned. Some of the antislavery sermons preached at the society’s meetings were later published, and exerted a strong influence on future abolitionists.32

Though the slavery report states that Dwight nurtured pro-slavery opinions in his students, the charge is an insinuation, contrary to the evidence. Even a cursory canvass of Yale’s graduates uncovers many antislavery men, far more than a real hotbed of pro-slavery opinion (such as Yale is supposed to have been) could have possibly produced.

“Yale, Slavery and Abolition’s” conclusions about the Dwight matter, at least, are not faithful to primary historical sources. Good history needs to be. The report’s writers have placed argument above investigation, and theory above fact. The wise reader will inquire for himself.

By Marena Fisher, Graduate ’91

© 2002 The Yale Standard Committee

read more

Read More

North

Driving Slavery from the North

Around the time of the Revolutionary War, many Americans began to realize that slavery was indefensible.

“Yale, Slavery, and Abolition” rightly points out the ubiquity of slavery in colonial New England: slavery was permitted in all thirteen original colonies. Many eighteenth-century Yale professors, graduates and donors owned slaves, and some Yale funds undoubtedly derive at least in part from slave labor.

However, around the time of the Revolutionary War, many Americans began to realize that slavery was indefensible. Quakers had openly opposed slavery for years, but now others, including many Yale men, began to speak out. Even setting aside antislavery men mentioned by the slavery report, there is not space here to adequately review Yale’s part in driving slavery from the North and resisting its movement into the western territories.

In 1773-1774, Ebenezer Baldwin (Yale, 1763) joined with Jonathan Edwards, Jr. (Princeton, 1765) in publishing a series of antislavery articles in The Connecticut Journal and the New-Haven Post-Boy. They declared:

“Has it not a shrewd appearance of inconsistence, to make a loud outcry against the British Parliament for making laws to oblige us to pay certain duties, which amount to but a mere trifle for each individual; when we are deeply engaged in reducing a large body of people to complete and perpetual slavery?”1

Levi Hart (Yale, 1760) pointed out the same inconsistency in a 1774 sermon entitled Liberty Described and Recommended . . . . He urged the Connecticut assembly to prohibit the importation of slaves, as Rhode Island had:

“Can this colony want motives from reason, justice, religion, or public spirit, to follow the example? When, O when shall the happy day come, that Americans shall be consistently engaged in the cause of liberty, and a final end be put to the cruel slavery of our fellow men?”2

New England assemblies began to respond to protests like these. A few weeks after Hart gave his sermon, Connecticut banned slave importation. In 1784, it passed a gradual emancipation law. In 1788, Jonathan Edwards, Jr. and Levi Hart led Connecticut’s Congregational ministers in petitioning the legislature to ban the slave trade, and their petition was successful. Though economic and military motives had a part in eliminating slavery in the North, mounting public outcry was important.3

“The Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom and the Relief of Persons Unlawfully Holden in Bondage” was formed in 1790 because many of Connecticut’s leading citizens were dissatisfied with the state’s limited and slow emancipation measures. The Society was made up largely of Yale men. Yale members included Noah Webster (Yale, 1778), Chauncey Goodrich (Yale, 1776), Zephaniah Swift (Yale, 1778), Levi Hart (Yale, 1760), Uriah Tracy (Yale, 1778), Simeon Baldwin (Yale, 1781), Timothy Dwight (President of Yale, 1795-1817), and many others.4

This association joined other antislavery groups in memorializing Congress for the abolition of the slave trade, and it also tried to bring about the complete abolition of slavery in Connecticut. Even though it failed in the latter purpose, some of the antislavery sermons delivered and published by the Society proved to be highly influential when a general abolition movement was born in the 19th century. Jonathan Edwards, Jr. and Timothy Dwight’s brother Theodore Dwight delivered perhaps the most powerful of these addresses.5

In 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance. Article Six of the Ordinance, which outlawed the transportation of slaves into the Northwest Territory, was probably included at the behest of Manasseh Cutler (Yale, 1765).6 It set an important precedent for restricting the movement of slavery into the western territories.

By 1804, all the states from Pennsylvania north had passed emancipation laws, and in 1807 Congress banned the slave trade, though slavery still grew and prospered in the South.7

Bacon

“If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong”

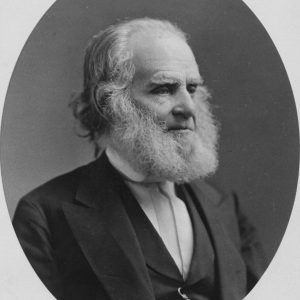

Leonard Bacon

Leonard Bacon spoke and wrote against slavery, and in 1846 he published a compilation from which Abraham Lincoln’s famously declared, “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”

Leonard Bacon

(1802 – 1881)

“If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong”

As “Yale, Slavery and Abolition” records, some graduates of Timothy Dwight’s Yale, such as John C. Calhoun and Samuel F. B. Morse, were in fact defenders of slavery. But giving Dwight credit for their opinions is a stretch, if for no other reason than that many of his students, and the students of his successors at Yale, were staunchly opposed to slavery.

Timothy Dwight foresaw that slavery would be eliminated in the United States, but the fulfillment of his vision tarried. Three years after his death, the 1820 decision to receive Missouri as a slave state proved that the “peculiar institution” was far from dead, and roused many northerners to oppose slavery publicly.

Jeremiah Evarts, Secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and a graduate of Dwight’s Yale, published in 1820 a series of antislavery articles in his board’s journal, The Panoplist and Missionary Herald.

The student Society of Inquiry Respecting Missions at Andover Seminary held formal discussions on slavery, and assigned Leonard Bacon (Yale, 1820) to write a report on the subject. Bacon later testified that in doing his research, he found “nothing . . . . more helpful” than Evarts’s articles. He was also strongly influenced by Jonathan Edwards Jr.’s fiery 1791 sermon The Injustice and Impolicy of the Slave Trade, and of the Slavery of the Africans.1

Bacon’s slavery report was printed and circulated, then published in revised form in New Haven’s Christian Spectator. In 1825, he returned to New Haven to become pastor of the Center Church. Later, along with Yale tutor Theodore Dwight Woolsey (later Yale President, 1846-1871), and three other young men, he formed both “The Anti-Slavery Association,” and a benevolence organization called the “African Improvement Society.” The Improvement Society helped organize schools, a library, and a savings bank for African Americans, and supported New Haven’s first black church, the Temple Street Church, then pastored by Simeon S. Jocelyn. The board of the Improvement Society included both blacks and whites, and thus constituted a direct challenge to racial prejudice in the city.2

Leonard Bacon continued to speak and write against slavery, and in 1846 he published a compilation of his work titled Slavery Discussed in Occasional Essays. The Dictionary of American Biography says about Bacon’s book:

“This fell into the hands of a comparatively unknown lawyer in Illinois, Abraham Lincoln. A statement in the preface made a profound impression on the future emancipator: ‘If that form of government, that system of social order is not wrong,—if those laws of the southern states, by virtue of which slavery exists there and is what it is, are not wrong, nothing is wrong.’ The sentiment reappeared in Lincoln’s famous declaration, ‘If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.’”

Lincoln credited the book with shaping his mind on the issue of slavery.

Some even in Leonard Bacon’s own congregation opposed his antislavery activities, but about this he said: “I make no complaint—all reproaches, all insults endured in a conflict with so gigantic a wickedness against God and man, are to be received and remembered, not as injuries but as honors.”3

Silliman

“the sin and shame of slavery...”

Benjamin Silliman

“A sense of integrity alone induces me to record these painful facts regarding the participation of our family in the sin and shame of slavery….”

Benjamin Silliman

(1779 – 1864)

Benjamin Silliman (1779-1864) was born into a family holding slaves, but grew to hate slavery and publicly oppose it. His diary and letters are full of denunciations of slavery, and an autobiographical sketch he wrote during the Civil War includes an honest confession of the wrong as it existed in his family:

“I regret to record that there were slaves . . . under our roof. . . . [T]here were house-slaves in the most respectable families, even in those of clergymen in the now free States; and those who fought for their country [in the Revolutionary War], of whom our father was one, did not appear to have felt their own inconsistency . . . .

“A sense of integrity alone induces me to record these painful facts regarding the participation of our family in the sin and shame of slavery . . . our nation is now settling an awful account with heaven for the accumulated guilt of more than two centuries, for which we are paying the heavy penalty of our blood.”1

Though Silliman, like Abraham Lincoln, initially supported the colonization of former slaves in Africa, like Lincoln, he later realized that this was not the answer to slavery. At the death of John C. Calhoun (for whom Calhoun College is named), Silliman recorded his grief at his former student’s defense of slavery: “He in a great measure changed the state of opinion and the manner of speaking and writing upon this subject in the South, until we have come to present to the world the mortifying and disgraceful spectacle of a great republic—and the only real republic in the world—standing forth in vindication of slavery. . . .” In this same meditation he wrote about slavery, “It is in better hands than man’s; and I trust that ultimately the colored men of all races on this continent will be received into the great human family as rational beings, and as heirs of immortality. While I mourn for Mr. Calhoun as a friend, I regard the political course of his later years as disastrous to his country and not honorable to his memory . . . .”2

Amistad

Yale’s Role in the Amistad Rescue

Yale had a role in obtaining the captives’ release, and it is hard to imagine how it could have had a greater part.

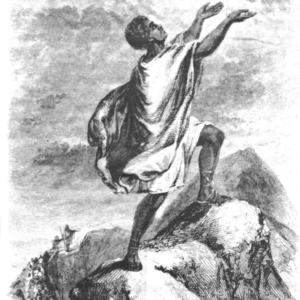

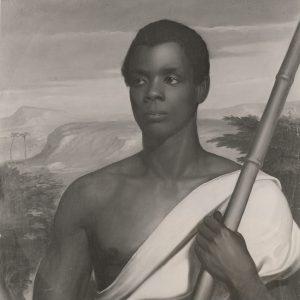

Joseph Cinque

Painted from life by Nathaniel Jocelyn in New Haven

The “Amistad” incident, dramatized in Steven Spielberg’s movie, is familiar to most New Haveners. In 1839, West Africans illegally sold into slavery in Cuba were put on the schooner “Amistad” to be shipped to a port on the other side of that island. While at sea, they overpowered their captors and tried to return to Africa, but through a series of mishaps ended up off the coast of Long Island, where they were taken into custody by a revenue cutter. They were brought to the New Haven jail, and held for trial.

The Spanish government demanded the Africans’ return to their so-called owners, and President Van Buren was all too eager to comply. Fortunately, abolitionists became interested in the case.

“Yale, Slavery and Abolition” concedes that Yale had a “minor” role in obtaining the captives’ release, but it is hard to imagine how the college could have had a greater part. Joshua Leavitt, a member of the original “Amistad Committee” that obtained legal representation for the Africans, was a graduate of Yale. Though the prosecution team was composed of Yale men, so was the entire defense team.1

Another Yale man, Josiah Willard Gibbs (Professor of Sacred Literature at the college, and one of Timothy Dwight’s students) weakened the prosecution’s case by locating an interpreter for the Africans so that their story could be told in court.2 Roger Sherman Baldwin (Yale, 1811), the key lawyer for the defense, was patriot Roger Sherman’s grandson and came from a family with a tradition of antislavery activism stretching back to 1773.3

Though the slavery report implies that the Yale men supporting the captives were simply interested in getting rid of them by sending them back to their native land, the historical record clearly shows otherwise. George E. Day, a Yale Divinity instructor, supervised the captives’ education, and Divinity students taught them English and the Bible. A couple of Yale students gave as much as five hours a day between them to working and talking with the Africans, and at least one, Benjamin Griswold (Yale Div., 1841) became a missionary in Africa partly because of his experience with them. Several Yale graduates, including Thomas H. Gallaudet (Yale, 1805), Leonard Bacon (Yale, 1820), worked to liberate the captives.4

Though it was John Quincy Adams’s successful argument before the U. S. Supreme Court that finally freed the Amistad victims, Yale men protected them and paved the way for their release.

Partly because of his work on behalf of the Amistad captives, Roger Sherman Baldwin was elected governor of Connecticut in 1844. In an address to the legislature he urged enfranchisement for African Americans, and a law to restrict slave catching in the state, but neither proposal was approved.5

Dwight

“O happy state! ... Where none are slaves, or lords; but all are men...”

Timothy Dwight on Slavery

“The white population of this country is universally free. This I trust, will ere long be true of the black population.”

Timothy Dwight

(1752 – 1817)

“O happy state! the state, by HEAVEN design’d . . .

Where none are slaves, or lords; but all are men . . . .”1

Timothy Dwight on the United States, and freedom:

“The white population of this country is universally free. This I trust, will ere long be true of the black population. In 1810, near two hundred thousand of these people had been emancipated, or been born in a state of freedom. The number is annually increasing. The disposition to emancipate slaves, and the conviction that they ought to be emancipated, are gaining ground; and there is no reason to doubt that they will spread wherever slaves are holden. In every other respect our freedom is as entire as that of any country, ancient or modern.”2

Timothy Dwight and Southern slavery:

To Benjamin Silliman when he considered taking charge of an academy at Sunbury, Georgia:

“I advise you not to go to Georgia. I would not voluntarily, unless under the influence of some commanding moral duty, go to live in a country where slavery is established….”3

“President Dwight, on one occasion, in illustrating [African Americans’] good qualities, spoke of a negro woman, in his family, who was often consulted as to the management of his family concerns. Amused by this eulogy, some of my classmates laughed outright; when the Doctor broke out upon them: ‘If I thought, young gentlemen, that you would have as much good judgment and good sense as my servant woman has, I should have a higher opinion of you than I now have.’ There was no more laughing.”

(William C. Fowler, Yale Class of 1816)4“Supreme memorial of the world’s dread fall;

O slavery! laurel of the Infernal mind,

Proud Satan’s triumph over lost mankind!”5

sources

Sources

1. Antony Dugdale, J. J. Fueser and J. Celso de Castro Alves, Yale, Slavery and Abolition, ([New Haven], The Amistad Committee, Inc., 2001), p. 29.

2. Charles E. Cuningham, Timothy Dwight 1752-1817: A Biography, (New York, Macmillan, 1942), pp. 293-334; James B. Reynolds, et al, Two Centuries of Christian Activity at Yale, (New York, G. P. Putnam Sons, 1901), pp. 51-70, 211-216.

3. Dugdale, et al., pp. 12-14, 29-30.

4. Dugdale, et al., p. 32, p. 44, n. 84; p. 33.

5. Dugdale, et al., p. 41, n. 5. See also: www.yaleslavery.org/whoYaleHonors/dwight2.htm & www.yaleslavery.org/whoYaleHonors/je.htm

6. For a portion of the executor’s report, see William C. Fowler, The Historical Status of the Negro in Connecticut, (New Haven, Tuttle, Morehouse; Taylor, 1875), pp. 121-122.

7. Cuningham, p. 336.

8. Dugdale, et al., p. 14.

9. Timothy Dwight, The Charitable Blessed: A Sermon, Preached in the First Church in New-Haven, August 8, 1810, (New Haven, Sidney’s Press, 1810), p. 20.

10. Dwight, The Charitable Blessed, p. 20.

11. Dwight, The Charitable Blessed, pp. 20-21.

12. Dwight, The Charitable Blessed, pp. 21-23.

13. Dwight, The Charitable Blessed, pp. 22-23.

14. Cuningham, p. 336.

15. Timothy Dwight, The Duty of Americans, at the Present Crisis, Illustrated in a Discourse, Preached on the Fourth of July, 1798, (New Haven, Thomas and Samuel Green, 1798), p. 30.

16. Dugdale, et al., pp. 13-14.

17. Timothy Dwight, Greenfield Hill: A Poem in Seven Parts, (New-York, Childs and Swaine, 1794), part II, ll. 193-214, some lines omitted.

18. Dwight, Greenfield Hill, pt. II, ll. 199-201.

19. Dwight, Greenfield Hill, pt. II, ll. 213-218.

20. Dwight, Greenfield Hill, pt. II, ll. 223, 228, 249-250, 253-257.

21. Dwight, Greenfield Hill, pt. II, ll. 268, 260; notes to part II, L. 208.

22. Timothy Dwight, Remarks on the Review of Inchiquin’s Letters, (Boston, Samuel T. Armstrong, 1815), p. 81.

23. Dwight, Remarks, p. 86.

24. Dugdale, et al., p. 14.

25. Dwight, Remarks, p. 81.

26. David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1966) pp. 57, 262-273; see also his The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823 (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1975), pp. 196-212, 256-257, 317.

27. Dwight, Greenfield Hill, notes to part I, L. 296.

28. Dugdale, et al., p. 12.

29. Yang, Jia Lynn, “Yale Slavery Report Questioned by Experts,” Yale Daily News CXXIV:65, p. 4.

30. Simeon Baldwin to Nathan Strong, Febr. 4, 1794; Minutes of a meeting of the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom, Sept. 11, 1794. Baldwin Family Papers, Group 55, Series I, Box 5, Folders 82, 84. Manuscripts and Archives, Sterling Library, Yale University.

31. Green’s Register for the State of Connecticut: with an Almanack, for the year of Lord, 1792, (New London, T. Green & son, [1791]), p. 65.

32. Leonard Woods Labaree, comp., The Public Records of the State of Connecticut, from May 1793 through October 1796, (Hartford, Connecticut State Library, 1951), pp. xviii-xx; Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North, (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 201-202; James D. Essig, The Bonds of Wickedness: American Evangelicals Against Slavery 1770-1808, (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1982), pp. 112-113; Mary Stoughton Locke, Anti-Slavery in America from the Introduction of African Slaves to the Prohibition of the Slave Trade (1619-1808), (Boston, Ginn & company, 1901), pp. 126-127.

1. As quoted in Roger Bruns, ed., Am I Not a Man and a Brother: The Antislavery Crusade of Revolutionary America 1688-1788, (New York, Chelsea House Publishers, 1977), p. 294; see also Kenneth Pieter Minkema, The Edwardses: a Ministerial Family in Eighteenth-Century New England, (Ann Arbor, UMI, 1988), pp. 507-509, 522, n. 109-110. Minkema asserts that the October 8, 1773 piece is by Edwards alone, and that the 1774 articles are by Baldwin. Jonathan Edwards, Jr. was the son of the Jonathan Edwards for whom the residential college is named.

2. As quoted in Bruns, ed., p. 347.

3. Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North, (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 107-108, 123-124, 156-157. See also Mary Stoughton Locke, Anti-Slavery in America from the Introduction of African Slaves to the Prohibition of the Slave Trade (1619-1808), (Boston, Ginn & company, 1901), pp. 40-41; and Minkema, The Edwardses, pp. 508-509.

4. List of society members is in Green’s Register, for the State of Connecticut: with an Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord, 1792, (New-London, T. Green & son, [1791]), pp. 64-67.

5. Leonard Woods Labaree, comp., The Public Records of the State of Connecticut, from May 1793 through October 1796, (Hartford, Connecticut State Library, 1951), pp. xvii-xx; Locke, Anti-Slavery in America, pp. 99, 103-104, 126-127, 141; Minkema, The Edwardses, pp. 509-512; Zilversmit, The First Emancipation, pp. 201-202.

6. Article on Manasseh Cutler, American National Biography Online: www.anb.org/articles/08/08-00341-article.htm

7. Zilversmit, p. 226; Locke, Anti-Slavery in America, pp. 148-156, 158-159.

1. Robert Cholerton Senior, New England Congregationalists and the Anti-Slavery Movement, 1830-1860, (Ann Arbor, University Microfilms Inc., [1954]), pp. 34-36.

2. Senior, New England Congregationalists, pp. 36-39. See also Robert Austin Warner, New Haven Negroes: A Social History, (New York, Arno Press, 1969), pp. 46-47. Authorities give varying dates for the foundation of “The Anti-Slavery Association” and the “African Improvement Society.”

3. Dictionary of American Biography, (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928), p. 481.

1. George Park Fisher, Life of Benjamin Silliman, (New York, Charles Scribner and Company, 1866), I, pp. 21-22.

2. Fisher, Life of Benjamin Silliman, II, pp. 98-99.

1. Franklin B. Dexter, Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College with Annals of the College History, (New York, H. Holt and company, 1885-1912), v. 6, pp. 673-678.

2. Clifton H. Johnson, “The Amistad Case and its Consequences in U. S. History.” Journal of The New Haven Colony Historical Society 36:2 (Spring 1990), pp. 3-22.

3. Samuel W. S. Dutton, An Address at the Funeral of Hon. Roger Sherman Baldwin February 23, 1863, (New Haven, Thomas J. Stafford, 1863), pp. 7-8.

4. African Repository and Colonial Journal, 15 (November 1839), pp. 317-318; American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Missionary Herald 39:12 (December 1843), p. 449; Howard Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad (New York, Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 81, passim; http://amistad.mysticseaport.org/librar

5. Robert Austin Warner, New Haven Negroes A Social History, (New York, Arno Press, 1969), p. 95.

1. Timothy Dwight, Greenfield Hill: A Poem in Seven Parts, (New-York, Childs and Swaine, 1794) part VII, ll. 127, 136.

2. Timothy Dwight, Travels in New England and New York, (Cambridge, Mass., The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1969), v. IV, p. 367.

3. George Park Fisher, Life of Benjamin Silliman, (New York, Charles Scribner and Company, 1866), I, p. 92.

4. William C. Fowler, The Historical Status of the Negro in Connecticut, (New Haven, Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1875), pp. 131-132.

5. Timothy Dwight, Greenfield Hill: A Poem in Seven Parts, (New-York, Childs and Swaine, 1794) part II, ll. 258-260.