Evolution:

Could Random Forces Have Invented the Marvelous Eye?

Her evolutionary biology class made her so unhappy, my friend said. The professor decided to lecture not just science, but attitude, too. For two lectures, she jabbed at the very idea of a creator, sneering at those who would embrace one. The podium was hers, and my friend, one among a hundred listening, could do little more than sit uncomfortably and hope for the end.

As teachers of science, it is only reasonable for professors to present things as precisely as possible. To present evolution as fact, not theory, is no small shift of emphasis; that shift could alter one’s whole world view.

Evolution: Could Random Forces Have Invented the Marvelous Eye?

Her evolutionary biology class made her so unhappy, my friend said. The professor decided to lecture not just science, but attitude, too. For two lectures, she jabbed at the very idea of a creator, sneering at those who would embrace one. The podium was hers, and my friend, one among a hundred listening, could do little more than sit uncomfortably and hope for the end.

I, too, remember being frustrated in biochemistry when evolutionary principles would be called on, uncontested, to explain life processes. It bothered me enough that one day, I called up the courage to ask the professor outright, “Why?” Why have biologists placed evolution among the inviolable truths of life? As I understand it, it is still unproven theory. Why wasn’t it presented as theory? One sentence to this point would have at least been fair. I can’t remember what the professor exactly replied, but it wasn’t satisfying.

As teachers of science, it is only reasonable for professors to present things as precisely as possible. To present evolution as fact, not theory, is no small shift of emphasis; that shift could alter one’s whole world view.

Naturalistic Macro-Evolution

I refer here to one narrow strain of evolution, which Darwin first offered to the world in The Origin of Species in 1859, naturalistic macro-evolution.

Naturalistic macro-evolution holds that impersonal forces driven by chance are responsible for the inception of life and the diversity of life on Earth today, including you and me. It explains all life without the aid of any intelligent power beyond the scope of the material universe. At its purest, it allows nothing outside the material realm: everything comes from natural processes occurring according to observable, physical laws. At most, it concedes that if God exists, he doesn’t matter one bit to us.

This particularly is what I mean by “evolution.” To begin to broach all the hybrid theories of “guided macro-evolution” would open fields of debate this essay is not intended to cover. Though perhaps a narrow definition, naturalistic macro-evolution has the profoundest impact today, not the least because most biology professors subscribe to it today, and many, many students accept it wholesale.

People more qualified than I have written books detailing problems with naturalistic macro-evolution, such as its mathematical improbability, or the incredible gaps in the fossil record. A fleshed out discussion could easily fill several tomes. I do not pretend to have the definitive word on the topic. For any objection I have, an evolutionist can think of some response, and then a non-evolutionist may answer the response, and so forth.

As with anything beyond our present grasp, whether be it metaphysical or simply outside the reach of scientific tools, the human mind can jockey justifications for its beliefs forever. Nevertheless, I do have a few thoughts to express.

Mutations

For naturalistic macro-evolution, mutations are bedrock. Darwin’s theory on a large scale is that thousands and millions of small changes in genes each conferred the slightest bit of advantage to organisms, so they flourished and eventually become a new species altogether. Over millions of years, according to current thought, a reptile began to take on mammalian characteristics, such as hair, and warm-bloodedness, and live-birth of offspring, and eventually became what we now know as a mammal. The changes had to be tiny steps, or else it would not be evolution.

If a mouse were born from a snake egg, that would be closer to creation by divine intervention than evolution. Or even on a level lower, if a chameleon were to give birth to little chameleons having a feathered wing, that too would be more miracle than Darwinian evolution.

But how then, does a tiny change give advantage? Does one-half percent of a wing help or hinder? If a chameleon’s leg were to become slightly wing-like, wouldn’t it be hindered from scurrying across the sand, and climbing up bushes, actually making it more vulnerable?

Or as the famous evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould once asked healthily, “What good is five percent of an eye?” Some have answered that five percent of an eye is good for five percent sight. But five percent of a physical eyeball does not give you five percent sight. To have any sight

requires, in addition to the physical eye, vision processing equipment neurons for intake of outside stimulus, and neurons to process the signals. Did all these areas of the organism mutate slightly by chance, at the same time and in the same direction, millions and millions of times to become the magnificently remarkable and complex eye we have today?

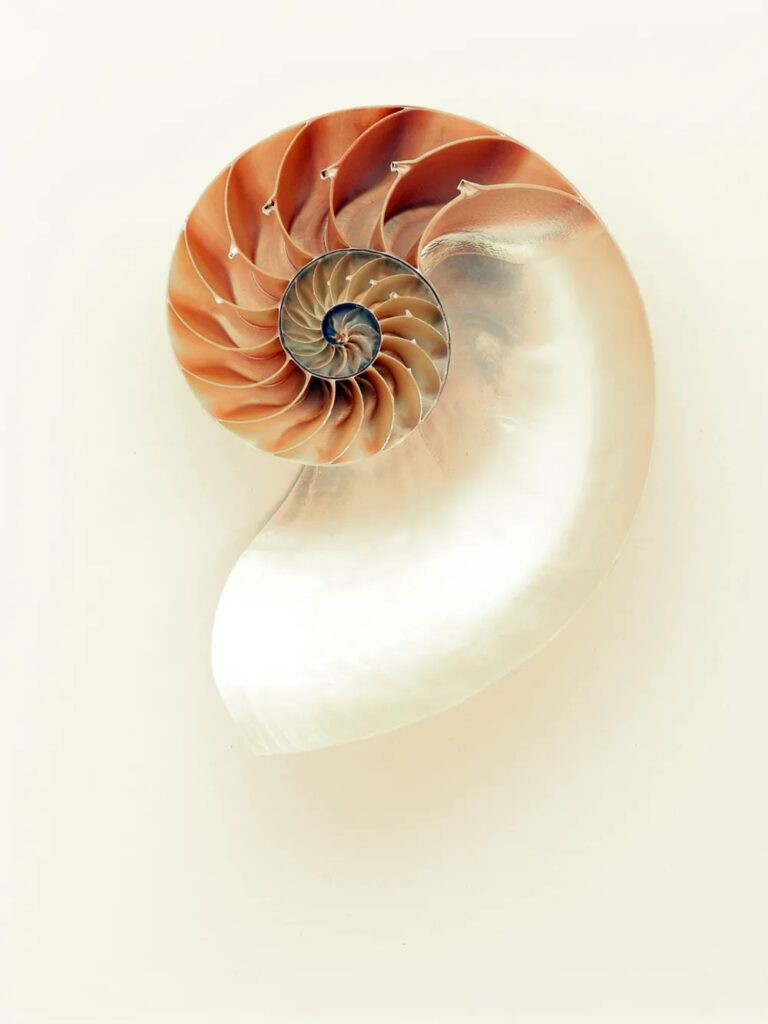

Another issue is raised when we consider the nautilus, a sea creature that in hundreds of millions of years of existence has yet to develop a lens for its retina, which according to the eminent evolutionist Richard Dawkins, it cries out for. If the mutational mechanism is powerful enough over Earth’s history to form the amazing human eye and many other eyes (some Darwinists agree there are at least forty evolutionary lines for the eye), why couldn’t it form a single lens on a nautilus in all that time?

As the Nautilus grows and matures, it secretes a new chamber towards the open end of its shell and seals off the old section with a wall called a septum, resulting in a whole new physiology of buoyancy and mobility.

Fossil Record

If mutational theory is evolution’s bedrock, the fossil record is its banner. Everyone has seen artist depictions of a pre-human human based on a fragment of some hundred thousand-year-old skull. Everyone has seen the imprint of the Archaeopteryx, half-reptile, half-bird, with its neck forever wrenched backward. And there are others here and there that look to be “between” species. Darwinism posits innumerable transitionals that have since died out, replaced by more complex variants of itself.

In relation to the fossil record, Darwinism stands or falls on whether the fossils representing vast periods of time reveal thousands and thousands of transitionals. Darwin said himself, “The number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great.”

But a close look at the record to date shows convincingly that “between” species are exceptions rather than rules, though the exceptions receive all the press coverage, in textbooks, in newspapers, in the classrooms, and in the papers of paleontologists. Where are the transitionals?

They should be everywhere. Given the estimated 10 million species on earth (with assuredly thousands in the depths of the seas and the earth as yet unknown), having evolved through time from a single bacteria, and the 130 years of fossil hunting since the Origin of Species came out, transitionals should be so numerous, that single fossils such as the Archaeopteryx really shouldn’t attract such focused attention.

And who has yet explained the “Cambrian explosion,” the appearance of nearly all the animal phyla 600 million years ago without any adequate evolutionary precedents? In fact, the fossil record spoke so resolutely against gradual development that some Darwinists in the 1970’s developed an adjunct theory called “punctuated equilibrium” to explain it, saying only the margins of a population change to become a new species (which is why transitionals do not show up in the fossil records), after which it rejoins at once the former population.

The well-known evolutionist Gould and a colleague authored the theory because, in his own words, “The history of most fossil species includes two features particularly inconsistent with gradualism: 1. Stasis (of species)… 2. Sudden appearance (of species).” I will only say here that punctuated equilibrium is controversial among biologists.

The Intelligence Of It All

If we step back and consider the millions of processes that support a self-sustained organism in perfect concert, with eyesight and all the interconnections and capacities in the brain that accompany it, with hearing and everything that accompanies it, with smell, with digestive abilities, with muscular contraction and expansion, with excretory abilities, it is hard not to notice the intelligence of it all.

Everything works so smoothly together to let a monkey jump from tree to tree, and to make a pianist run his fingers across a keyboard and bring out a sonata. Even yet, for an amoeba to swallow a paramecium, or a single bacteria to sustain itself, tens of thousands of processes must work together. Was all this intelligent complexity ground out by impersonal forces over time? Do the laws of nature hold some hidden genius to effect something so incredible as a living organism?

We can ponder genes and DNA for hours, and never get over how marvelous the system is. It is mind-boggling to think of all the proteins shaped according to genetic information, with the perfect mix of van der Waals forces and electrostatic attractions to twist around into that perfect shape to become things that combine into mitochondria and other organelles, and regulate materials that pass between sections of the cell, and even help the DNA, its creator, to replicate, or form other proteins.

Any cell biologist will tell you that a single cell in your body can be as complex as New York City on New Year’s Eve. If you focus your microscope onto a cell and observe, you find mitochondria working to churn out ATP, and organelles of odd sorts and shapes swimming in various directions all to the beat of life. And for everything visible, there are thousands of molecular interactions invisible.

How could intelligence arise out of chaos? Robots show an intelligence. They can be programmed to put doors on car chassis, or bring medicine down a hospital hallway to patients. They can show intelligence because they have an intelligent engineer that created it.

The most complex of robots are nothing next to the layers of complexity of the simplest life system. Can the genius of genetic coding not have a mind behind it? The famous cosmologist, Sir Fred Hoyle, once said that the first living organism emerging by chance from a chaotic mix of chemicals is as likely as “a tornado sweeping through a junkyard might assemble a Boeing 747 from the materials therein.”

Conclusion

Darwin was just a man, like you and me. Certainly, he owned a keen intellect, but he wasn’t a super-man. Observing animal life on the Galapagos, he began to formulate a theory of how things became the way they are. He conjectured, scratched out lines of thought, tried to fill in gaps by using logic and imagination, without performing one empirical test—he did it all by deduction. This is the scientific way.

But like you and me, he was capable of error, of stretching too far on a certain point. And like our judgements, his should be open to honest criticism. Darwinism is a scientific theory, an extremely elegant one, but nevertheless a theory that should be treated as such. It is a little strange to me why it has achieved the status of the sacred, why high school teachers give it out as grade school teachers do the multiplication table, and college professors find it appropriate to express emotional hostility to those that oppose it, namely, those who believe in a divine Maker.

Besides, for all the apparent logic in Darwinism, what’s really more logical, that I, with my body, with all my emotions and mental capabilities, with all my longings for God, arose from a bacteria, or that God shaped me with His hands?

Taejoon Ahn, Jonathan Edwards ’96

(Much debt is owed to Philip Johnson’s Darwin on Trial, Regnery Gateway, Washington, D.C., 1991.)

“Resolved, To live with all my might while I do live.”

After graduation, Edwards spent several years first as pastor of a small Presbyterian parish in New York City, then as a tutor at Yale where he was able to continue his studies in philosophy, the natural sciences (he wrote his paper on spiders then) and theology. Yet growing increasingly unsatisfied with purely academic endeavors, and desiring to occupy himself with concerns more directly touching the spiritual welfare of people, he sought God for a break into a new situation.

The break came in the fall of 1726 when the church in Northampton (also in the Connecticut river valley in central Massachusetts, where his highly-regarded yet aging grandfather Solomon Stoddard was preaching) invited him to take up residence as assistant pastor. Northampton would be his home for the next 23 years, and the place with which his name would be indelibly connected.

Stoddard had ably led the people of Northampton, who by then consisted of about 200 families, for the past 56 years, having overseen five special spiritual awakenings in the town. Of these times, Edwards recalled, “I have heard my grandfather say, the greater part of the young people seemed to be mainly concerned for their eternal salvation.” Unbeknownst to Jonathan as yet, history would prove that these special occasions had only been primers for what would come under his own pastorate.

Before telling the story of the Northampton revival, it should be mentioned that less than a year after his arrival, Edwards married Sarah Pierpont, whom he probably first spied in a meetinghouse when he was a tutor at Yale. Though she was only thirteen when he first saw her, he noted her as “a rare example of early piety.” Four years later, they were married, and would continue in their loving bond for thirty years until Edwards’ death. As one early biographer wrote, “Perhaps no event of Mr. Edwards’ life had a more close connection with his subsequent comfort and usefulness than this marriage.”

It was in the winter of 1734 that, as Edwards narrates, “the Spirit of God began extraordinarily to set in, and wonderfully to work amongst us: and there were, very suddenly, one after another, five or six persons, who were to all appearances savingly converted.” With that opening salvo from God, a widespread concern among people for their own spiritual condition swept through Northampton. Similar events had been transpiring in towns throughout the river valley and other parts of Massachusetts and Connecticut.

The effect was immediate and deep. In his Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, Edwards writes, “When once the Spirit of God began to be so wonderfully poured out in a general way through the town, people had soon done with their old quarrels, backbitings, and intermeddling with other men’s matters. The tavern was soon left empty and persons kept very much at home.”

Further, “our public assemblies were then beautiful: the congregation was alive in God’s service, everyone earnestly intent on the public worship . . . the assembly in general were, from time to time, in tears while the Word was preached: some weeping with sorrow and distress, others with joy and love.”

While pressing home the consequences of sin, and shrinking in no way from the Scriptural fact of hell, Edwards and other preachers held out Jesus’ salvation through faith alone. As people wrestled with their eternal condition, they found relief in Christ. Edwards wrote, “The town seemed to be full of the presence of God; it never was so full of love, nor joy, and yet so full of distress, as it was then.”

Within six years, this spiritual fire would catch throughout all the colonies and also across the Atlantic through the preaching of George Whitefield and John Wesley. Northampton in 1734 was lapping at the heels of a period that historians would later call “The Great Awakening” for the generality and intensity of people’s concern for their eternal salvation.

Edwards’ Faithful Narrative played a critical role in informing a largely ignorant wider public, both in the Colonies and in England, of what was happening in Northampton. The account helped inspire a new crop of English revivalists, notably Wesley, towards effecting similar spiritual blessings in England.

By 1742, however, the revival had dissipated into, as one eyewitness wrote, “strife and faction,” in large part because of the emotional excesses that had crept into congregations. Edwards recognized the danger of substituting for the true conversion experience mere “wildfire” and “enthusiasm,” and labored to keep such “irregularities” to a minimum. While recognizing the profundity of God’s work in a life, he maintained the need to keep a steady state of mind.

While enemies of the Awakening seized the excesses to condemn the whole of what happened, Edwards kept a measured assessment. He wrote, “there may be some mixtures of natural affection . . . some imprudences and irregularities, as there always was, and always will be in this imperfect state, yet as to the work in general . . . they have all the clear and incontestable evidences of a true divine work.”

In May of 1747, Edwards met a young veteran missionary whose extraordinary work among the American Indians he had been reading about. Although by this time David Brainerd was nearly overcome by tuberculosis, his acquaintance with Edwards in the remaining five months of his life proved to be significant, if for no other reason than that it would lead to a biography that would energize a slumbering missionary movement both in the Colonies and abroad.

Converted at the height of the Great Awakening while a student at Yale, Brainerd was the unfortunate object of the ire of the college government after he criticized the spiritual quality of one of his tutors. Though at the top of his class, and despite his submission of an apology, he was denied his degree. (This widely perceived injustice became a significant motivation for the formation of Princeton College.)

Without a degree, yet full of faith in God, he interviewed with members of the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, who determined he was the man of their choice to bring the Gospel to the American Indians.

Working among the Kaunaumeek and Delaware Indians in New Jersey, Brainerd persisted for years with no visible result from his preaching. But in the summer of 1745, when he was physically worn and discouraged to the point of quitting, an awakening came among the New Jersey Indians that was, as one historian put it, “one of the most remarkable in Christian history.”

Deeply moved by Brainerd’s death, Edwards felt it his duty to put his story on paper. The biography soon gained an international following and was the first American-printed biography to do so. Over the next hundred years it would do more to raise Christian consciousness about missionary work than any book of its era.

A New England minister who had an especially difficult parish to shepherd told about the help he derived from The Life and Diary of the Rev. David Brainerd in these terms: “and when we shut the book we are not praising Brainerd, but condemning ourselves, and resolving that, by the grace of God, we will follow Christ more closely in the future.”

Edwards’ contact with Brainerd would prove to be of more than personal interest, but preparatory for his own missionary work among the Indians of Stockbridge, Massachusetts just a few years later.

His move to Stockbridge in 1751 was, in fact, the result of a sad conclusion to a doctrinal controversy in his parish. His grandfather had established the practice of allowing those who were not professedly Christians to take part in the church communion. After careful study of Scripture and much prayer, Edwards found himself unable to accept this practice as Biblical, and proceeded to limit the communion table to only those who were expressly converted.

This overturning of tradition caused a great stir in the town, and particular leading families who had harbored other resentments against Edwards seized the opportunity to try and dismiss him as their pastor. Remaining calm and steady through the whole affair, Edwards reasoned with the people, but to no final effect.

By a majority vote of the ruling council, Edwards’ relationship with the Northampton parish was dissolved. It was then that Edwards answered a pastoral call from an outpost town in western Massachusetts called Stockbridge. There he preached to the white settlers and the Housatonic Indians, as well as set up schooling for both white and Indian children. Whatever time he had left he put into his writings. In this way, Edwards spent the last years of his life.

In 1755, the trustees of the recently established College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) called upon Jonathan Edwards to take over the presidency. Hesitating at first, he eventually acceded to their pleas. However, illness would intervene at the outset of his term as president. In 1758, after receiving a smallpox vaccination that was too strong, he died at the age of 54, having lived a full life of service to God.

Leaving a legacy of service, and writings that would become classics in Christian literature, Edwards plainly fulfilled his old college resolution to “live with all my might.” One other resolution he formed back at Yale was, “Resolved, To strive every week to be brought higher in religion, and to a higher exercise of grace, than I was the week before.” So he did, from day to day and week to week, for the sake of his Savior, and blessed us all.

Steve Ahn, JE ‘96

© 2000 The Yale Standard Committee

O sinner! consider the fearful danger you are in! It is a great furnace of wrath, a wide and bottomless pit, full of the fire of wrath that you are held over in the hand of that God whose wrath is provoked and incensed as much against you as against many of the damned in hell. ...And now you have an extraordinary opportunity, a day wherein Christ has thrown the door of mercy wide open, and stands in calling and crying with a loud voice to poor sinners; a day wherein many are flocking to him, and pressing into the kingdom of God. Many are daily coming from the east, west, north and south; many that were very lately in the same miserable condition that you are in, are now in a happy state, with their hearts filled with love to him who has loved them, and washed them from their sins in his own blood, and rejoicing in hope of the glory of God. How awful is it to be left behind at such a day! To see so many others feasting, while you are pining and perishing! To see so many rejoicing and singing for joy of heart, while you have cause to mourn for sorrow of heart, and howl for vexation of spirit! How can you rest one moment in such a condition? Are not your souls as precious as the souls of the people at Suffield, where they are flocking from day to day to Christ?

— Jonathan Edwards, from his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”