Amistad and Yale:

The Untold Story

One morning late in August 1839, a strange ship appeared off Culloden Point, Long Island. She was long, low, and weather-beaten, her sails battered and torn. A troop of blacks, outlandishly dressed and armed with long knives and muskets, seemed to be her crew.

La Amistad

1839

The U.S. Navy cutter Washington, alarmed by her odd appearance, overpowered the crew and towed the ship to New London harbor, hoping to claim salvage rights to her. After a pre-trial hearing, the blacks were sent to New Haven, the only nearby town with a jail big enough to hold all forty-three of them.

Amistad and Yale: The Untold Story

One morning late in August 1839, a strange ship appeared off Culloden Point, Long Island. She was long, low, and weather-beaten, her sails battered and torn. A troop of blacks, outlandishly dressed and armed with long knives and muskets, seemed to be her crew.

The U.S. Navy cutter Washington, alarmed by her odd appearance, overpowered the crew and towed the ship to New London harbor, hoping to claim salvage rights to her. After a pre-trial hearing, the blacks were sent to New Haven, the only nearby town with a jail big enough to hold all forty-three of them.

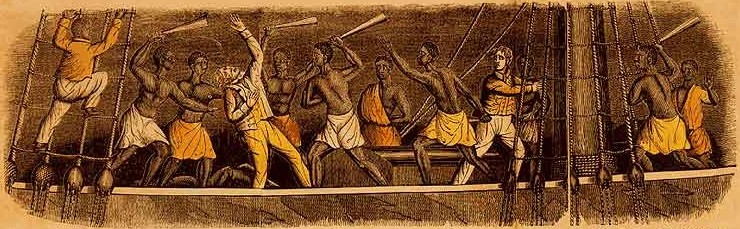

This story, long known to New Haveners, is now familiar to anyone who has seen Steven Spielberg’s movie Amistad. Amistad was the name of the mysterious schooner, and her crew a group of black freemen sold into slavery in West Africa. They were resold in Cuba, where the African slave trade was illegal. Then they pulled off a desperate mutiny against their Spanish captors while being shipped to sugar plantations on the other side of the island.

After the mutiny they pointed the ship back toward Africa, but under cover of night the Spaniard they had forced to pilot her turned her northwest, toward the United States. He hoped to land in a slave state and recover control of the vessel and the Africans. When she arrived off Long Island, the schooner had been at sea for sixty-three days.

It took almost two years from the time they were captured off Long Island for the Africans to recover their freedom, and their story became a dramatic episode in this country’s long struggle to abolish slavery.

A very high percentage of those who befriended them and helped in the fight for freedom were Yalies: graduates, professors, and students. The arrival of the Amistad Africans changed Yale, but it is also true that Yale was uniquely prepared to help and shelter them.

Though the movie Amistad doesn’t show it, what motivated most of those who took up the fight was faith in Jesus Christ and a desire to see His salvation come to the farthest part of the globe.

Practically the first to go into action on behalf of the Africans were Lewis Tappan, Simeon Jocelyn, and Joshua Leavitt, a group of abolitionists who formed themselves into an “Amistad Committee” to drum up monetary help and legal counsel. Once a Unitarian, Tappan had been brought to Christ through the prayers of his mother and the counsel of Lyman Beecher (Yale, 1797, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame). Tappan’s love of Christ had stirred in him a hatred of slavery, and he spent much of his time working to destroy it.

Leavitt (Yale, 1814) was a lawyer, editor of New York’s abolitionist paper, The Emancipator, and a close associate of Charles Finney, the great evangelist.

Jocelyn had been pastor of the first black church in New Haven, till he was driven from his post by persecution. Each man’s abolitionist fervor was a product of his belief that slavery, under God, was wrong.

The Amistad Committee asked Roger Sherman Baldwin (Yale, 1811) to defend the Africans. Baldwin was a grandson of Connecticut patriot and signer of the Declaration of Independence, Roger Sherman. Not long after passing the bar he had successfully argued in court for the freedom of a fugitive slave. In 1831, he had defied the wrath of a New Haven mob when he defended a proposal to build a black college near Yale.

Far from the youthful opportunist Spielberg’s movie shows him to be, Baldwin took the case hesitating to charge for his services at all, and constructed a defense that withstood legal challenges all the way to the Supreme Court. Seth Staples, another member of the legal team, and a founder of Yale Law School, accepted compensation only for expenses.

An unusual mixture of love and talent had to be applied to the case for the Africans’ cause to prevail. Droves of locals paid 12 and a half cents apiece to see the “strange” captives at the county jail, but few enough were genuinely concerned for them. One of those who did care was Yale Professor of Biblical literature Josiah Willard Gibbs. (This Gibbs was father to the famous Yale physicist for whom Gibbs lab is named.)

An unusual mixture of love and talent had to be applied to the case for the Africans’ cause to prevail. Droves of locals paid 12 and a half cents apiece to see the “strange” captives at the county jail, but few enough were genuinely concerned for them. One of those who did care was Yale Professor of Biblical literature Josiah Willard Gibbs. (This Gibbs was father to the famous Yale physicist for whom Gibbs lab is named.)

He was an austere man, quiet and cautious in his opinions. As a scholar, he had been much disappointed. A master Hebraist, he had twice undertaken to translate an important German edition of a Hebrew lexicon, only to be twice scooped by others when his work was partially completed. Rather than getting embittered, though, he broadened his grasp of languages, and became a true linguist.

The coming of the Amistad was for him “one of those events that bring a life into focus, summoning qualities that until such a moment… seem alien and useless.” The Africans needed a translator if their side of the story was to be told. Where in all New England would they find one?

In his visits to the jail, Gibbs discovered that their language was previously undescribed and that he must start from scratch to help them. Holding up his fingers one after another, he coaxed the Africans to count for him in their language. He worked at it till he could count up to ten without drawing their laughter. Working with the blacks showed him that they came from three main peoples and languages, but that most were Mende, a tribe from Sierra Leone.

His spare time found Gibbs at the docks in New Haven and New York, searching for a black face that might light up at his Mende numerals “e-ta,” “fe-le,” “sau-wa,”….

The translator he finally found, amazingly enough, was not only Mende but a Christian. As a boy James Covey had been kidnapped and enslaved, but was rescued by part of the British anti-slavery patrol off the coast of Africa. He found Christ and came to speak English at a missionary school in Sierra Leone, and had joined the anti-slavery patrol himself as a sailor on the H.M.S. Buzzard. The Buzzard was in New York to see some American slavers brought to justice.

Overjoyed, Gibbs returned with Covey to New Haven and caught the Africans at breakfast. They were ecstatic to at last have someone to whom they could tell their story. What they related, along with linguistic testimony from Gibbs, showed conclusively that they had been illegally transported to Cuba, and thus weren’t technically slaves at all.

The communication barrier was broken. Partly at the request of Cinque, leader of the mutiny, times were set aside for the Africans to learn English and the Bible. George Day, an assistant instructor to Gibbs at the Divinity School, was asked to teach, and with him came a Divinity student, Benjamin Griswold.

Day had taught for two years at the New York School for the Deaf and Dumb after graduating from Yale in 1833. Griswold was a personal friend of T. H. Gallaudet (Yale, 1805), a pioneer in education for the deaf. They brought special skills to the classes, and the Mende were soon writing touching, if initially halting, letters in English.

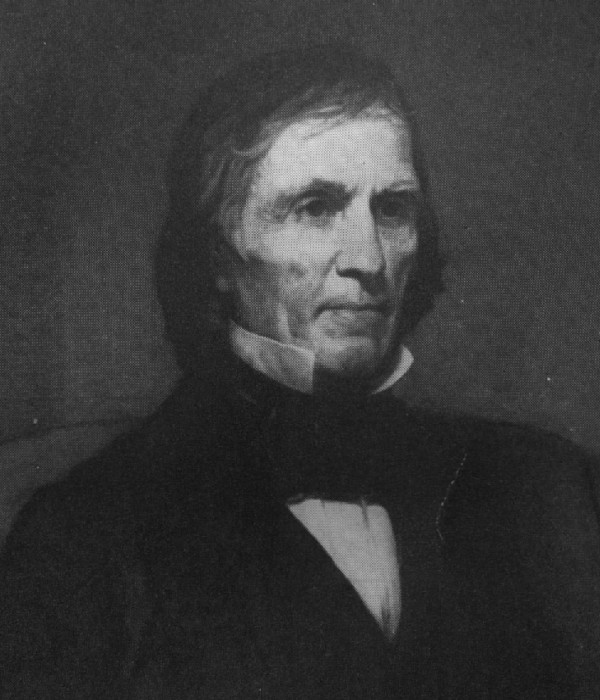

Griswold was enflamed by this opportunity to share Christ with those who had never heard of him before, and on Jan. 13, 1840, the very day the district court decided to free the Africans, he wrote a letter to his mentor Gallaudet to ask him for advice about going to Africa as a missionary. (The actual letter still survives in SML’s Mss. and Archives.)

Though the case was appealed to the Supreme Court and the Mende’s release was delayed, the willingness Griswold expresses in that letter to go to Africa at the call of God was not wasted. Less than a month after the Amistad captives departed for Sierra Leone, free at last, Griswold himself took ship for Gabon.

John Quincy Adams’ magnificent eleventh-hour defense of the Africans in the Supreme Court finally ended the legal battle. Lacking time and energy to prepare the case adequately, and beset with eye inflammation, the 73-year-old Adams felt an oppression upon him that dropped away only as he rose to argue the case.

He later noted in his diary that “the world, the flesh, and all the devils in hell are arrayed against any man who now in this North American Union shall dare to join the Standard of Almighty God to put down the African slave trade…” and wondered what more he “with a shaken hand, a darkening eye, a drowsy brain” might do against it. He asked only “to die upon the breach.” It took the Civil War to decide the issue with finality.

It is worth pondering how God used all this outpouring of love and faithfulness. Though the movie didn’t show this, five missionaries (two of them black) went with the Mende on their return to Africa. The American Missionary Association, which grew out of the Amistad Committee, founded not only an African mission, but many other foreign and domestic missions and schools besides. Many of the major black colleges, including Howard, Fisk, Atlanta, Talledega, and others, trace their origins to the Amistad events.

None of the participants in the Amistad affair could have seen what impact their steadfastness would have, but its effects are still with us today.

Marena Fisher, Graduate ‘92

© 1998 The Yale Standard Committee

Griswold

Benjamin Griswold:

Counting the Cost

In Africa he traveled farther than any other missionary of his time, seeking to reach interior tribes with the gospel of Christ.

Benjamin Griswold (Yale Div. 1841) had a fiancée in Hartford who, on hearing of his missionary call to Africa (see text), determined to go with him. Griswold took one last trip to New York to complete preparations for their voyage. While he was finalizing things, a telegram arrived stating that his beloved had suddenly died.

His mission board sent condolences and gently asked if his plans had changed. “I go, Sir” was his response. In Africa he traveled farther than any other missionary of his time, seeking to reach interior tribes with the gospel of Christ.

He himself died in 1844 after only two and a half years on the field. But a letter he wrote while still in the ship off the coast of Africa is revealing. Having just heard of the death of a fellow missionary on shore, he wrote that he had counted the cost before he left his native land, and that he expected when Jesus Christ had done with him in Africa, he would call him home in his own way and time. A question Griswold poses in one of his last letters could be asked today. In a trip to the interior he came across a tribe who asked for a missionary to be sent to them. Sadly, he told them there was no one to spare from the Gabon mission. “Who,” he asks those at home, “is ready and willing to come and point out to these, and others equally earnest, the way to heaven?”