Decision on Mount Hermon

Though many decades have passed since then, the effect the conference had on the students who participated and on many other people in countries around the world has scarcely been surpassed.

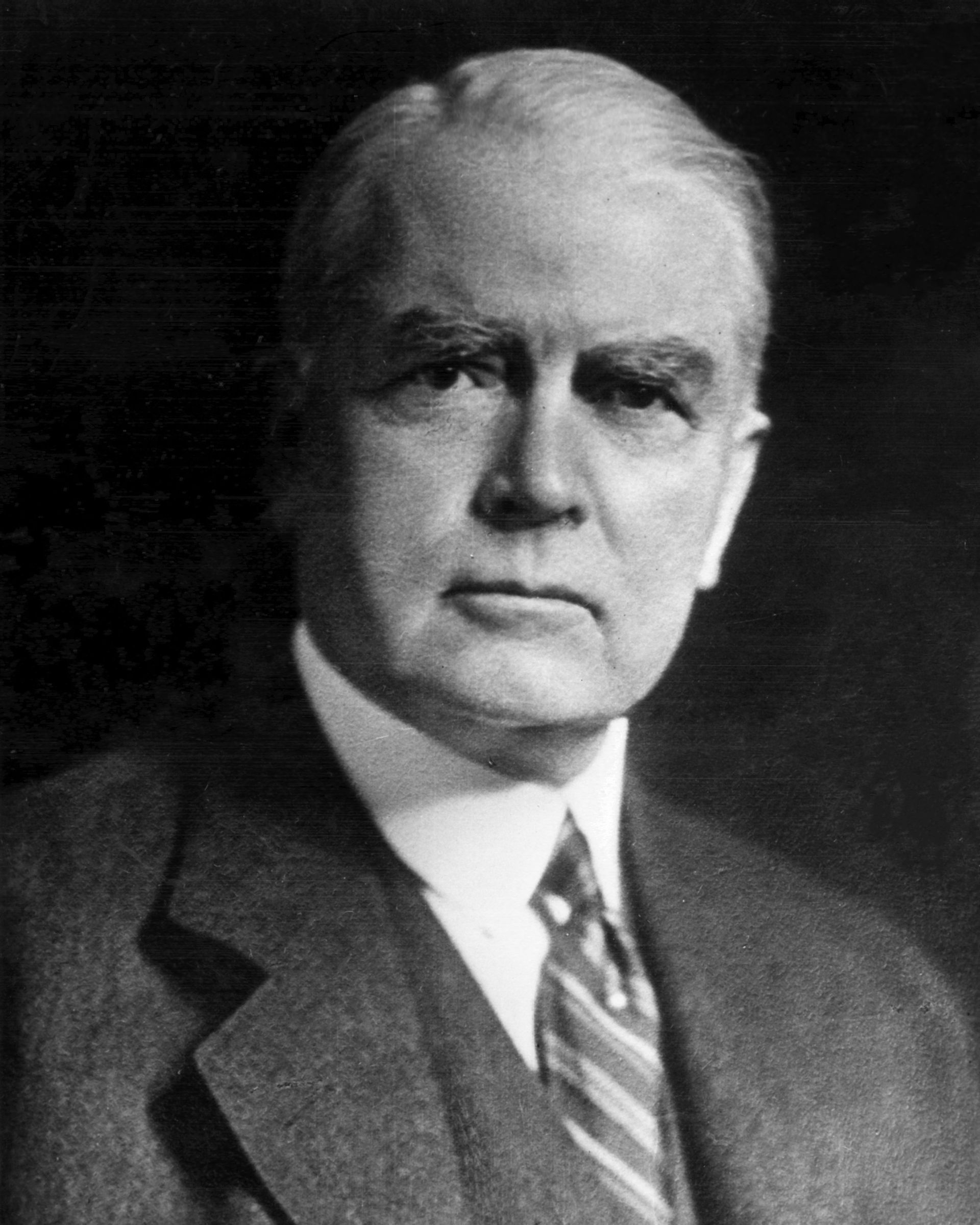

Dwight Moody

Mount Hermon, Massachusetts, has been waiting expectantly for years beside the Connecticut River, waiting for the Mount Hermon Conference to reconvene. Up to this day, however, it has not seen the like. Though many decades have passed since then, the effect the conference had on the students who participated and on many other people in countries around the world has scarcely been surpassed.

Dwight Moody had called the conference, the first national intercollegiate Bible study in America. Mr. Moody was one of the two or three most prominent evangelists in American history to that day, an unlettered ex-shoe salesman whose message commanded the attention of English nobility as easily as that of his beloved street urchins he cared for in Chicago.

To a generation resigned to an “every man for himself” approach to life, the immediate outcome of the Mount Hermon Conference may seem strange, though the actions taken were simple enough. By its close, 100 young men had decided to give their lives away in the bright New England summer of 1886.

John R. Mott, in later years a leader in what came to be called the Student Volunteer Movement, was a student then, and by his own reckoning the conference marked a decisive turn in the course of his life. What follows is excerpted from his first-person account, written down when he revisited Mount Hermon years later:

“There came together here at Mount Hermon in the month of July, 1886, 251 student delegates. We came from eighty-nine different universities and colleges. With nine of my fellow-students I came from one of the eastern universities, Cornell University.

“The leading universities of Canada were represented, likewise every section of the United States, unless it was the Pacific Coast. There were some quite large delegations, especially from Dartmouth, Amherst, Yale, Cornell, and Randolph-Macon, one of the colleges of Virginia.

“Among the delegates were a few professors and teachers, but speaking generally, it was an undergraduate gathering. We met for a period of four weeks…. We had one platform meeting each day, which was what we might call a double-header or a triple-header.

“Another feature of the daily program was the little company—little, I say, although before the conference was over it included nearly every delegate—which met for an hour every morning to discuss methods of carrying on work among our fellow students in the schools and colleges.

“In the long afternoons and in the early evening, often beneath these beautiful elm trees … I remember discussions about the superhuman work of Christ in conversion, about the principles that should guide one in choosing a lifework, about the second coming of our Lord. As a result of these many discussions under the trees, possibly even more than through public addresses, men’s doubts were dissipated,” and their faith became a reality.

“In the long afternoons and in the early evening, often beneath these beautiful elm trees … I remember discussions about the superhuman work of Christ in conversion, about the principles that should guide one in choosing a lifework, about the second coming of our Lord. As a result of these many discussions under the trees, possibly even more than through public addresses, men’s doubts were dissipated,” and their faith became a reality.

John R. Mott

“Another part of the daily program was the opportunity for personal fellowship. We roamed up and down this side of the river, and we crossed the river and climbed along the sides of the distant hills. Sometimes a man would go alone, again there would be two men; at times, a little larger company—it might be an entire college delegation.

“In my library at home … is a leather-bound notebook in which I wrote down very carefully full notes on all the sermons and addresses and discussions of those four wonderful weeks. I first took them down roughly, and then during the afternoons I copied them in ink, underlining with red ink the points that had most laid hold on me. Many delegates worked over their notes, not only copying them but applying them, reflecting upon them, saying, ‘What does this mean to me? What should this mean to others through me?’

“At the beginning of this conference nobody had thought of it as being a missionary conference. Several days had passed before the word missions was mentioned. If I remember correctly, over two weeks had passed before that great theme was suggested on the platform. But there were causes hidden in the background.

[At Princeton, a missionary’s son and daughter, Robert and Grace Wilder, had prayed that the Lord would use Mount Hermon to point many to become missionaries. Robert, a Princeton undergraduate, went to the conference, Grace prayed for it steadily at home. Back at her own college, Mount Holyoke, she was one of thirty-four young women who a few years before had signed a declaration—“We hold ourselves willing and desirous to do the Lord’s work wherever He may call us, even if it be in a foreign land.”]“So Robert Wilder began from the very first day at Mount Hermon to search for and find kindred spirits. He discovered Tewksbury of Harvard, and Clark of Oberlin, and one or two others and brought them together daily for united prayer.… They did not confine their meeting to those who had decided to be missionaries, but added others who were thinking seriously about the subject and who honestly wanted to face facts.… The men who attended those meetings found it impossible to pray without work. They could not pray for the world’s evangelization without dealing with the question of the missionary call.… Wherever you went you heard them talking about it.

[Meanwhile, July 16th saw the first missionary address in an evening meeting, and another followed within a week. That brings us to July 24th:]“Then came a meeting that I suppose did more to influence decisions than anything else which happened in those memorable days.… The speeches were short, not averaging more than three minutes in length. Each speaker made one point, the need in the country which he represented, the need for men to come out to help meet the crisis.

“We went out of that meeting not discussing the speeches. Everybody was quiet. We scattered among the groves.… I know many men who prayed on into the late watches of the night. The grove back there on the ridge was the scene that night of battles. Men surrendered themselves to the great plan of Jesus Christ [for] this whole world and … His Kingdom.

“We went out of that meeting not discussing the speeches. Everybody was quiet. We scattered among the groves.… I know many men who prayed on into the late watches of the night. The grove back there on the ridge was the scene that night of battles. Men surrendered themselves to the great plan of Jesus Christ [for] this whole world and … His Kingdom.

“The conference was drawing to a close when another meeting was held of which we do not talk much.… It was held in the old Crossley Hall. We were meeting there in the dusk. Man after man arose and told the reason why he had decided to become a volunteer. God spoke through reality. There was a lack of hypocrisy and of speaking for effect which gave God His opportunity to break through and give a message that men would hear. It was not strange, therefore, that during the closing hours the numbers of volunteers greatly increased.

“At the beginning of the Mount Hermon Conference fewer than half a dozen students were expecting to be missionaries. By the last day ninety-nine had decided and had signed a paper that read, ‘We are willing and desirous, God permitting, to become foreign missionaries.’ Ninety-nine had signed that paper. Mr. Wilder has the old record.

“The conference closed, but the next morning those ninety-nine met for a farewell meeting of prayer. As I recall, it was in a room in Recitation Hall. While we were kneeling in that closing period of prayer the hundredth man came in and knelt with us. So of 251 delegates, 100 decided that they were willing and desirous, God permitting, to give themselves to this great work of giving all men an opportunity to know Christ.

“Some of us saw that here was a fire that should spread, and one afternoon a number took a walk over the hills.…”

Robert Wilder and another man from Princeton spent the next year going from college to college, and indeed the fire spread. No one is sure of the number, but at least 16,600 students left their homes over the next five decades for overseas service as a consequence of the Mount Hermon Conference.

The 100 who volunteered that summer denied their own self-interest in order that Jesus Christ might be made known to men and women afar off, whom they had never met. Nothing in their story, however advocates self-denial for self-denial’s sake. Self-denial alone is devoid of content, a spiritual and natural dead end. What they chose is different and far better, for they denied themselves in order to present their every faculty, resource and time to the Lord Jesus Christ, and He did through them what could not have been done in any other way. As St. Paul said, many years ago:

“Therefore, I urge you, brothers, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God—this is your spiritual act of worship. Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.” (Romans 12:1-2)

“Therefore, I urge you, brothers, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God—this is your spiritual act of worship. Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.”

Romans 12:1-2