Frequent Revivals Mark Yale’s History

Yale’s history will show that for the great majority of its 300+ years, Yale was thoroughly different from what it is today.

(This was published in 1990 and is a shortened version of Yale’s History Shows Students Must Choose: Revival or Rebellion.)

Today the average Yale undergraduate goes through his four years of college thinking that Yale has always been more or less what it is now. He would be confirmed in this belief by every aspect of his undergraduate life. Yale’s history will show that for the great majority of its 300+ years, Yale was thoroughly different from what it is today.

Yale was first envisioned by John Davenport, who founded New Haven in 1638, intending to “drive things in the first essay as near to the precept and pattern of Scripture as they could be driven.” This Christian colony soon set aside land for a college “to fit youth … for the service of God in Church and Commonwealth.”

Ten ministers confirmed John Davenport’s dream by founding Yale in 1701. The first rector, Abraham Pierson, accepted the position, saying that “he durst not refuse such a service to God and his generation.” Under Pierson’s direction, the first Yale men met together twice a day for prayer, at sunrise and in the late afternoon.

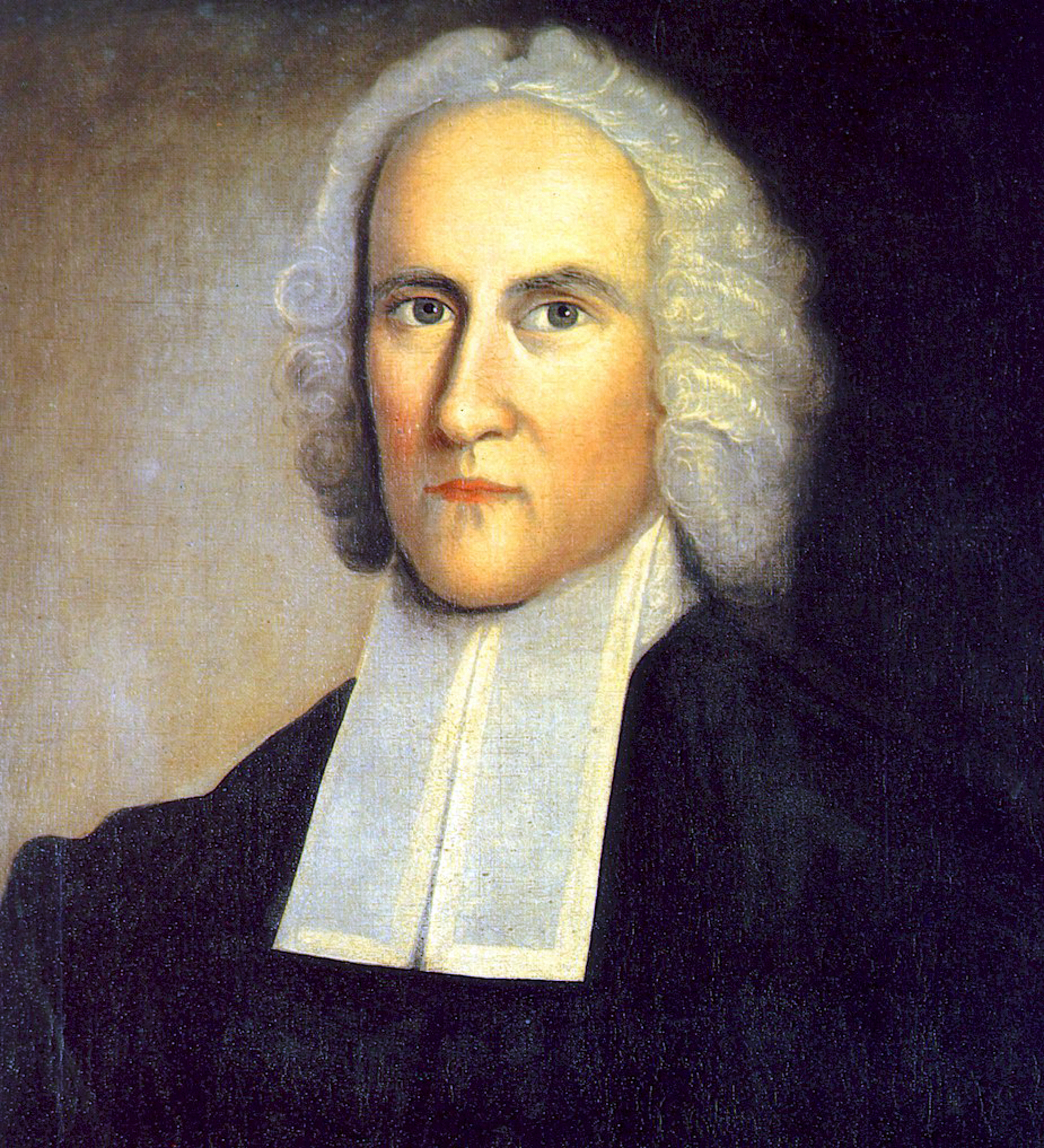

Yale was only a few years old when Jonathan Edwards entered the college at the age of thirteen. In 1720 he graduated from Yale with the highest honors at the age of seventeen. At graduation he was “filled with an inward, secret delight in God,” and he resolved “to live with all my might while I do live.” Jonathan Edwards played a major role in the Great Awakening, which transformed the country in 1740, and became “the most significant Protestant voice between the Reformation and the twentieth century.”

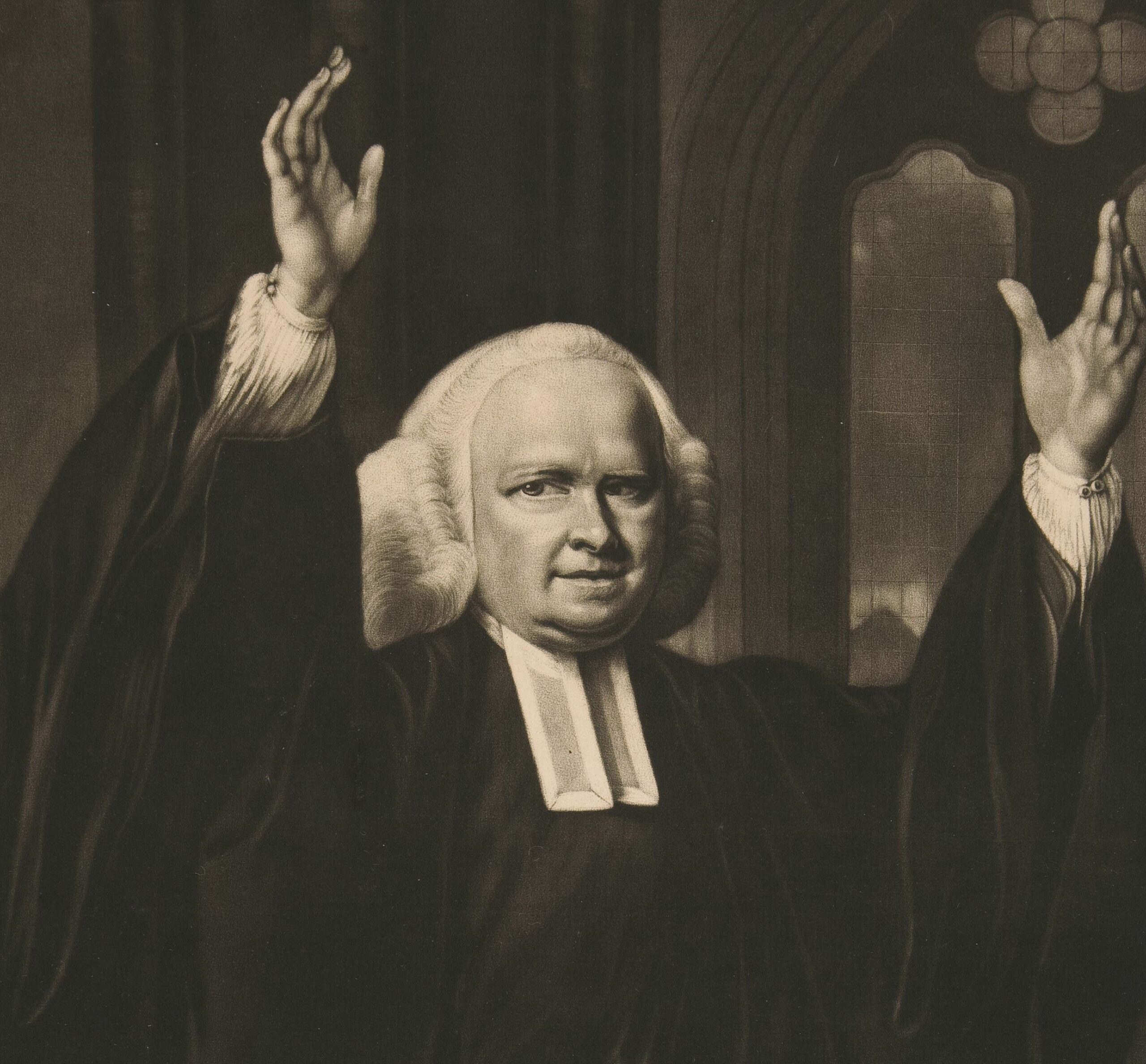

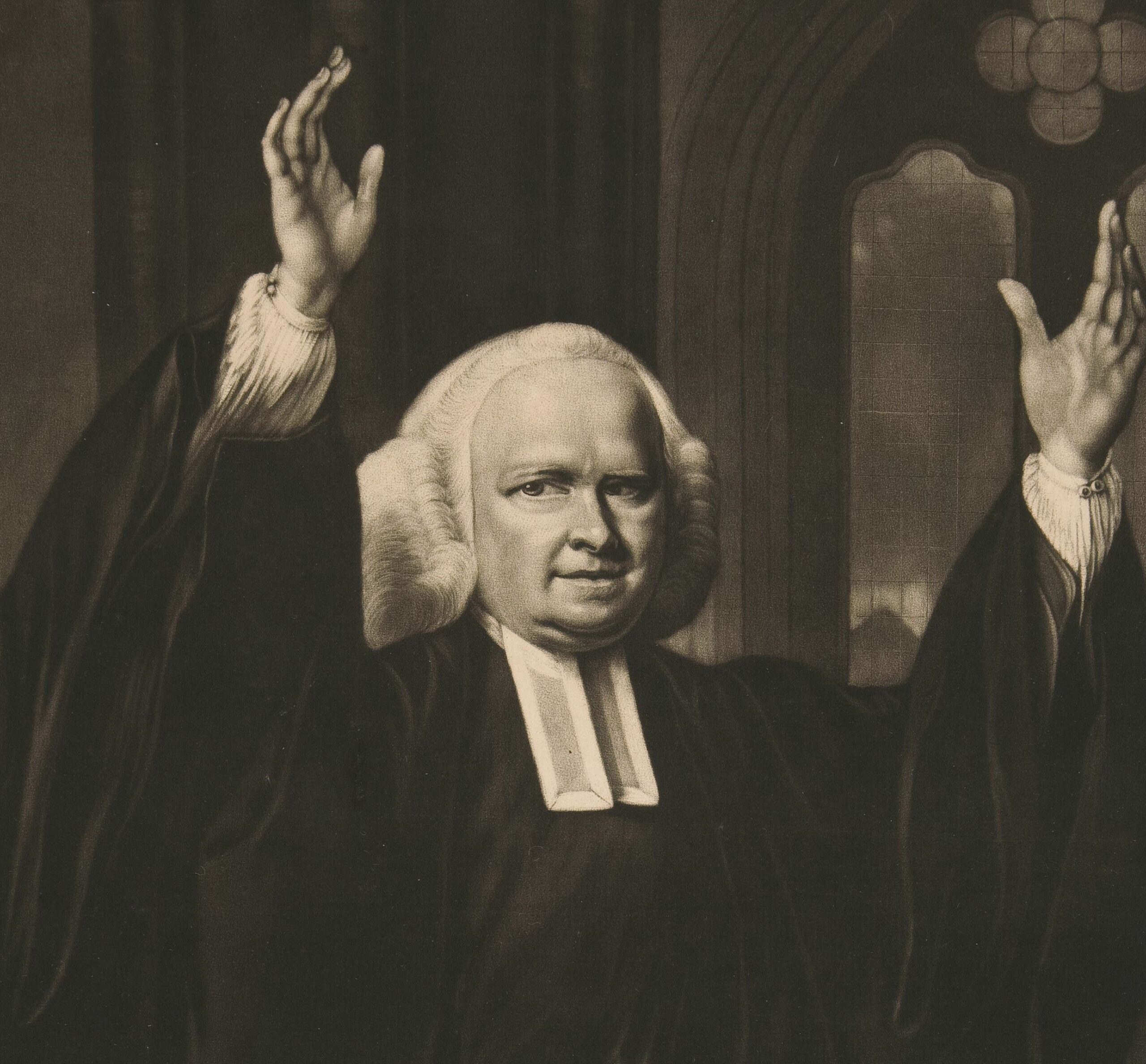

The famous English evangelist George Whitefield, then 25 years old, visited Yale during the Great Awakening. He preached to “enormous crowds” on New Haven Green and then at Center Church. The first Yale revival occurred the following spring. Its results were permanent; students professed an active and intense Christian faith for years afterwards.

The famous English evangelist George Whitefield, then 25 years old, visited Yale during the Great Awakening. He preached to “enormous crowds” on New Haven Green and then at Center Church. The first Yale revival occurred the following spring. Its results were permanent; students professed an active and intense Christian faith for years afterwards.

David Brainerd, a sophomore at the time, quickly became a spiritual leader in the Yale revival. Although tradition forbade speaking to upperclassmen unless first spoken to, Brainerd went from door to door, freely presenting the Gospel to every student on campus. After leaving Yale in 1742, he became a missionary to the Indians, who willingly left their former beliefs to receive Christ.

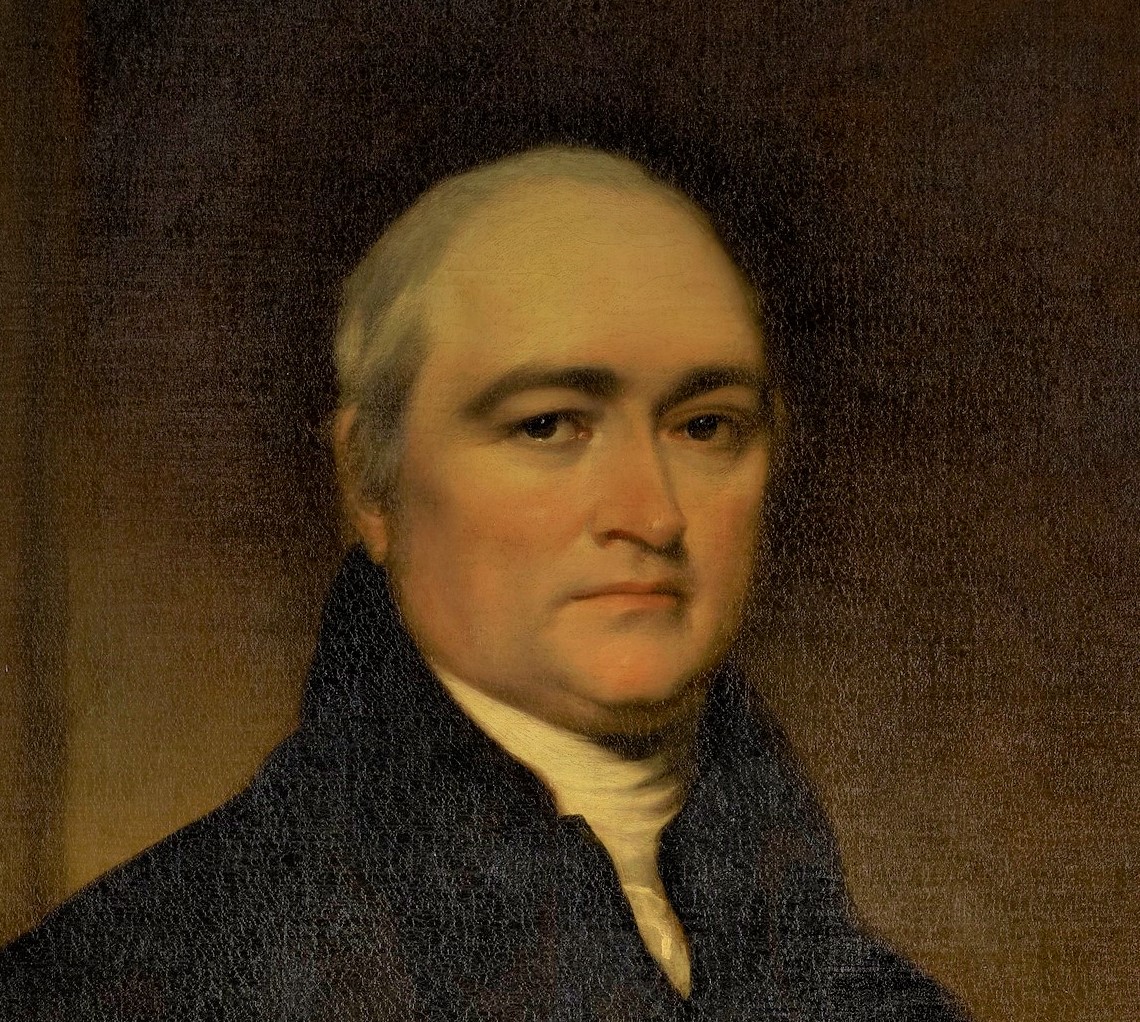

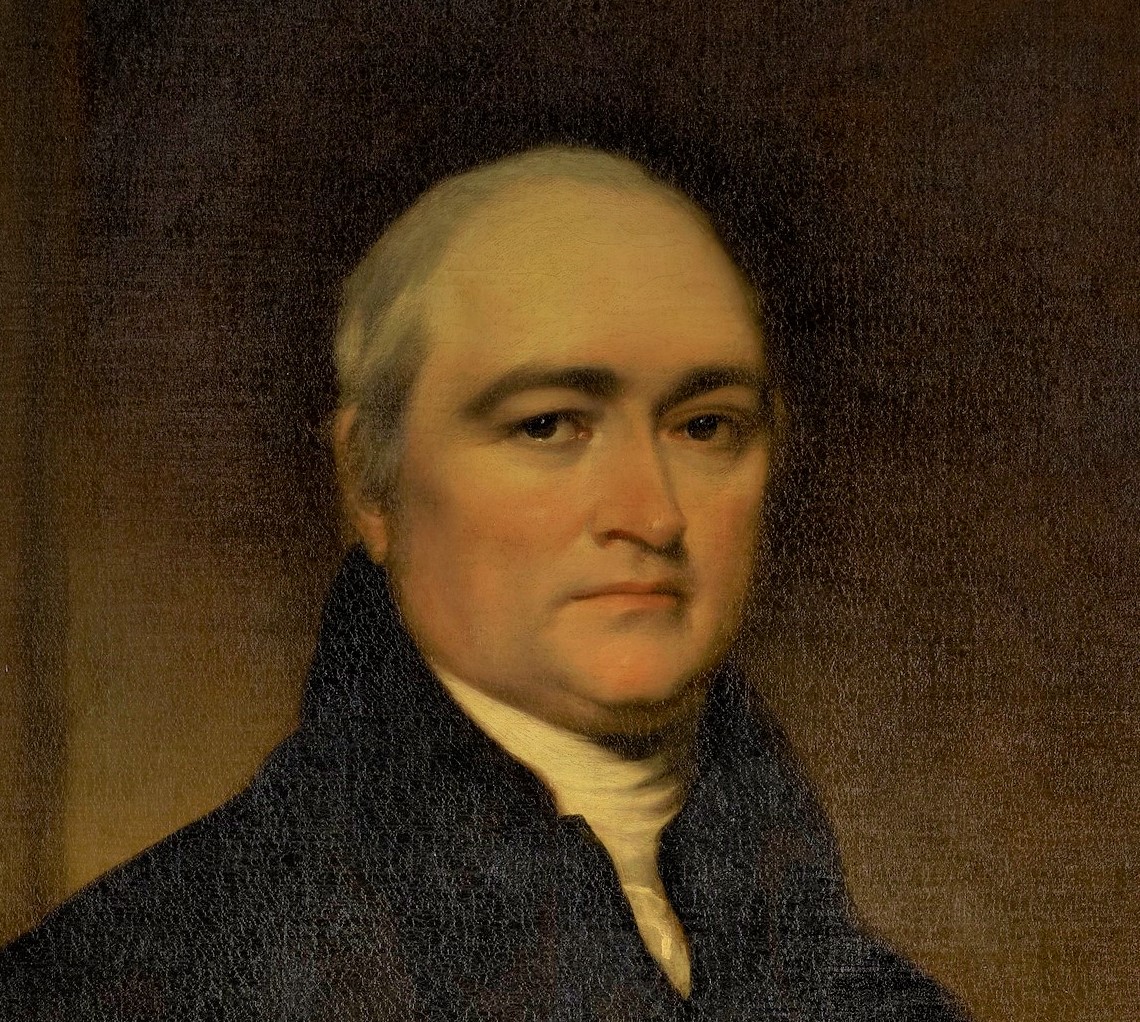

During the American Revolution, Ezra Stiles became president of Yale (1778). Stiles was a frequent visitor to the Jewish synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, one of three synagogues in all of America at that time. He invited every Jew who passed through New Haven to dinner at his house. He would go out of his way to meet a rabbi—He met five in his lifetime—and he often discussed with the suffering Messiah of Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53.

The “French Infidelity,” a philosophy born during the French Revolution, had obscured the Christian foundation of Yale when Timothy Dwight became president in 1795. “The frank and direct way in which he met and overcame the infidels immediately upon his accession was characteristic of the man. They thought the faculty were afraid of open discussion, but when they handed Dr. Dwight a list of subjects for class disputation, to their surprise he selected this: ‘Is the Bible the word of God?’ and told them to do their best. He heard all they had to say, answered them, and there was an end. He preached incessantly for six months on the subject, and all infidelity skulked and hid its head.” During his seventh year as president, Dwight saw a “quiet but thorough” revival begin among his students in 1802.

Timothy Dwight preached incessantly for six months on the subject [of "Is the Bible the word of God?"], and all infidelity skulked and hid its head.” During his seventh year as president, Dwight saw a “quiet but thorough” revival begin among his students in 1802.

Benjamin Silliman, an instructor at Yale during the 1802 revival, described the scene: “Yale College is a little temple; prayer and praise seem to be the delight of the greater part of the students while those who are still unfeeling are awed into respectful silence.” Silliman himself was converted during this revival. Soon afterward, he began counseling the newly-converted students and leading Bible studies. One biographer said of Benjamin Silliman, “Throughout the rest of his life the depth and sincerity of his religious convictions [from 1802] influenced all that he undertook. Only in this way was he able to accomplish the work which caused him to be described by another Yale president as ‘the father of American scientific education.’”

“Yale College is a little temple; prayer and praise seem to be the delight of the greater part of the students while those who are still unfeeling are awed into respectful silence.”

The revivals did not cease after Timothy Dwight died in 1817. The years 1820, 1821, 1823, 1824 and 1825 were each marked by spiritual awakenings among the students. The revival of 1827 was marked especially “by the conversion of a knot of very wicked young men, whose piety at a subsequent period became equally eminent.” The movement started at Yale and spread to New Haven; for every Yale man converted there were nine New Haveners converted. “Its effect upon student morals and order was so great that for a year not a single student was disciplined by the faculty.” Revival again swept over Yale in 1835, 1836 and 1841. The revival of 1841 was so important to the students that they cancelled the Junior Ball that year. A revival also began at Yale during the national revival of 1858.

“[The revival’s] effect upon student morals and order was so great that for a year not a single student was disciplined by the faculty.”

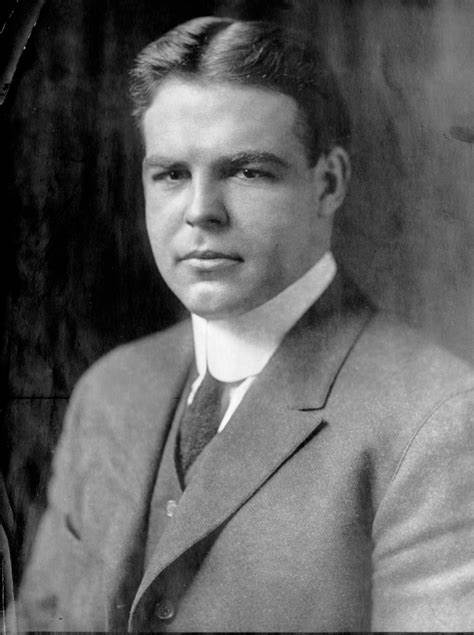

Beyond 1900, the career of William W. Borden (1909) saw the formation of Bible study classes totaling a thousand members out of 1300 undergraduates at Yale. Borden became a Christian early in life, and though he was a millionaire, decided to become a missionary. He came to Yale with that purpose in mind, but between that time and the mission field, he did a prodigious amount of work at Yale. He excelled as a student and a personal evangelist, founded the Yale Hope Mission for New Haven’s derelicts, began Bible studies and made it his habit to pick the least likely men on campus to talk with and invite to these meetings.

After working at a tremendous pace in America for three years after graduation, he spent the last year of his life in Egypt in missionary training. He died there of meningitis at the age of 25. Dr. Kenneth Scott Latourette, the renowned historian and one of Borden’s closest friends, said of him, “His rugged yet simple faith in Christ as Saviour and Lord, and in the Bible as God’s inspired Word, is a tonic to me.”

But by the 1920’s Yale had begun a different course. “The temper had changed beyond recognition from my student days,” he wrote. Latourette’s own life, however, was an outstanding exception to this trend. After graduating from Yale, he coordinated the thousand-man Bible studies for a time. He later went to the mission field in China, but illness forced him to return to the States. He eventually came back to Yale. “Here I saw dimly, but decisively, the divine purpose in my life,” he wrote later. Despite his fame as an historian—he wrote 83 books and received 17 honorary degrees—scholarship was secondary to him. His chief interest was students. For years he held a special Bible class for freshmen, and three informal groups of students met by the fireside in his study every week. He also took time for counseling—he dissuaded one young man from committing suicide and guided him into a new life in Jesus Christ. Until the end of his life in December 1968, Dr. Latourette considered himself a missionary and friend to the students at Yale.

With such a history of committed believers at Yale, men and women should be encouraged to seek revival again in our own time. “For I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ, for it is the power of God for the salvation for everyone who believes.” (Romans 1:16) This is the message which needs to be heard on Yale’s campus today. In the words of Professor Latourette: “What lies beyond this present life I cannot know in detail, but I know Who is there and am convinced that through God’s grace, that love which I do not and cannot deserve, eternal life has begun here and now, and eternal life is to know God and Jesus Christ whom He has sent.”

Regardless of the current spiritual climate, or the prevailing attitudes among Yale students today, God’s truth does not change, and He longs to turn hearts back to Himself. He only waits for those who will call upon Him in contriteness of spirit—to call upon His name, that now as in ages past, He might bring about His purposes.

“I stand in awe of your works, O Lord. Revive them in our day; in our time, make them known.” (Habakkuk 3:2)

“What lies beyond this present life I cannot know in detail, but I know Who is there and am convinced that through God’s grace, that love which I do not and cannot deserve, eternal life has begun here and now, and eternal life is to know God and Jesus Christ whom He has sent.”

Professor Kenneth Scott Latourette