After graduation, Pitkin entered Union Theological Seminary in New York. His love of serving God made him the natural spokesman for the cause of foreign missions not only within the institution, but in the churches of New York and Brooklyn and later in the colleges of New England. For three years, he challenged Christian students with the call to foreign missionary service, even going as far as the major colleges in the Midwest. These colleges in turn supplied the strength of the missionary movement in America at the turn of the century.

In 1895, Pitkin and those who had gone to other parts of the U.S. returned east to speak at Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York. “In Philadelphia,” G. S. Eddy wrote, “We prayed for deeper unity and greater power. On the morning of the last day, I remember hearing the saintly Peter Scott, then just returned from Africa, praying that Pitkin might be filled with greater blessing. I do not know how Pitkin spent the day. He was alone in prayer, and so were we. But I shall not forget hearing him that night. It was evident that something had happened between his soul and God. It was evident that the Spirit of God was upon him by the presence of Jesus Himself in all he said and did. It was a mass meeting of students and though it was already late, he held the entire audience with great power.”

After arousing missionary interest in the United States, Pitkin and his newly-wed wife went to China as self-supporting missionaries. Pitkin lived among the Chinese, learning their language, but he had not been in China long when a fanatical political-religious sect called the Boxers began to take over the country. Motivated by a hatred toward foreigners, they began to set fire to mission compounds and to kill Christian missionaries along with the Chinese associated with them.

In 1900, the Boxers had sealed off all exits from Paotingfu, the city where Pitkin was stationed. Despite the perilous situation, his love for the Chinese did not wane. A Chinese messenger managed to escape the city with Pitkin’s last wish for his wife and son who at that time were in Ohio: “Tell the mother of little Horace to tell Horace that his father’s last wish was that when he is twenty-five years of age, he should come to China as a missionary.”

On the first of July, through a pouring rain, a mob organized by the Boxers attacked Pitkin’s mission compound from the front and back. Pitkin attempted to defend the women and children in the mission, but the mob soon burst through the gate and captured Pitkin in the mission school yard. There, he was beheaded.

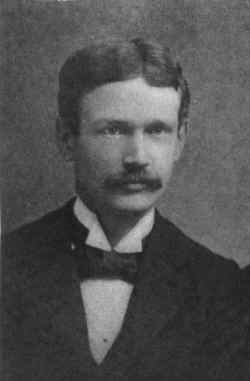

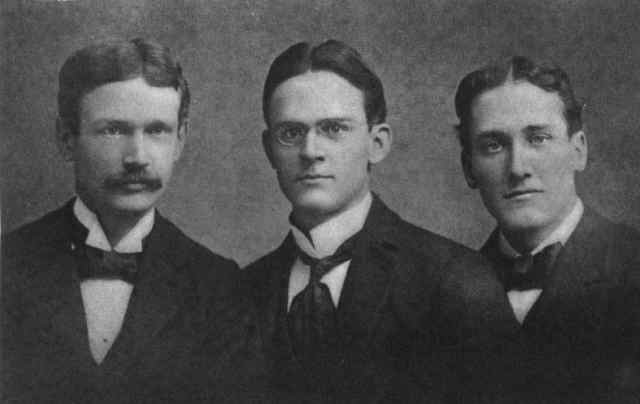

The earnestness and intensity of his whole-souled devotion to God led one peer to describe him thus: “Straight, strong, with a clear eye and sensitive mouth, whether in fun or in earnest, always doing with his might what he had found to do. Perhaps that was his most striking characteristic. He was no faultless saint. I have known more gentle, more lovable men, greater scholars, deeper thinkers, but never have I known any one with such power of translating faith into action. With him, to believe was to do.”

“Short as was his life, I never knew him to waste a moment of it.”

Yuna Lee, Saybrook ’94

Quotations taken from G.S. Eddy’s Horace Tracy Pitkin: Missionary, Advocate, and Martyr