The Greatest Columbian? You decide…

John Jay and Alexander Hamilton

Face to face across Columbia’s southeastern quad stand two buildings whose names affirm this College’s boast at having launched two great architects of America’s independence.

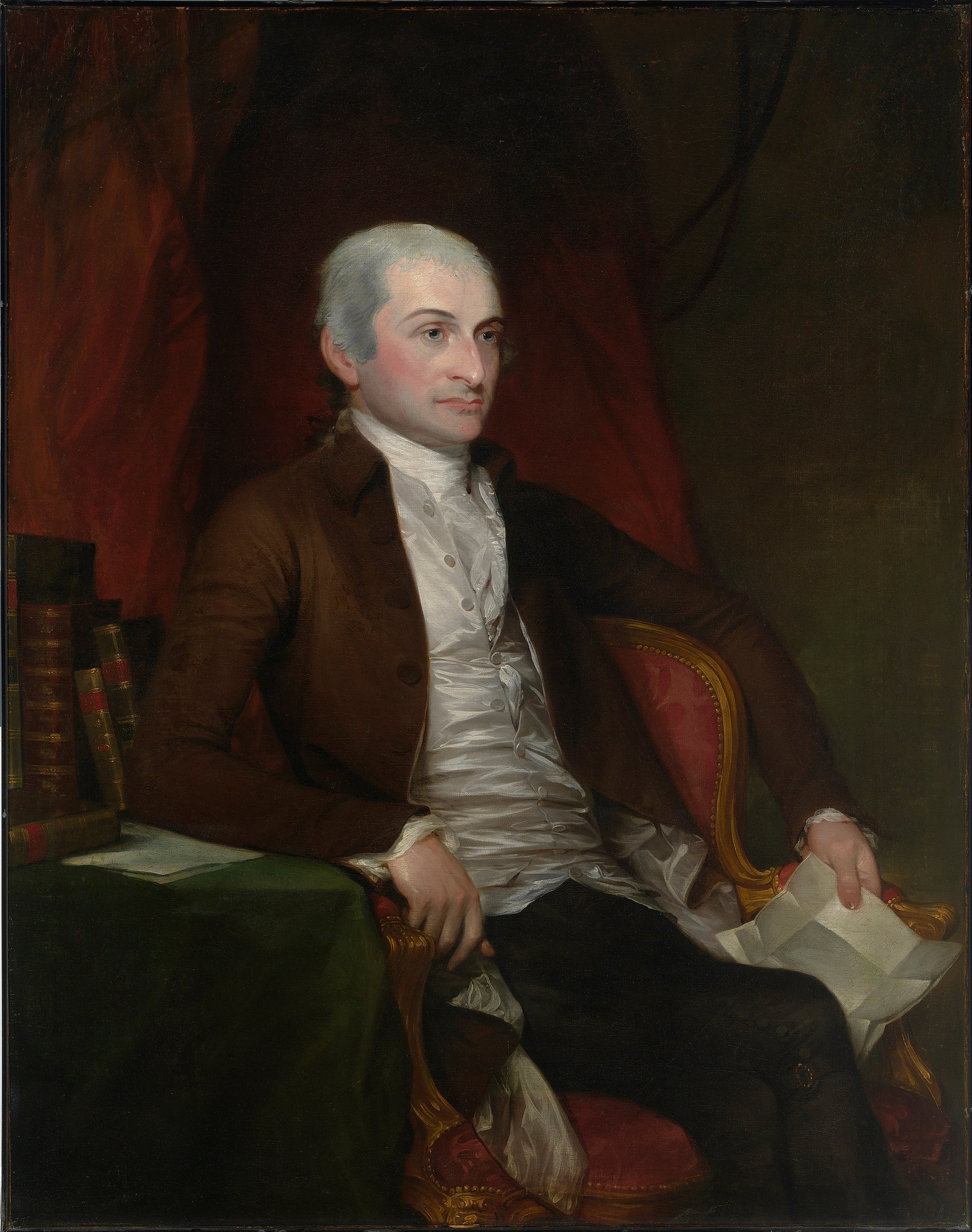

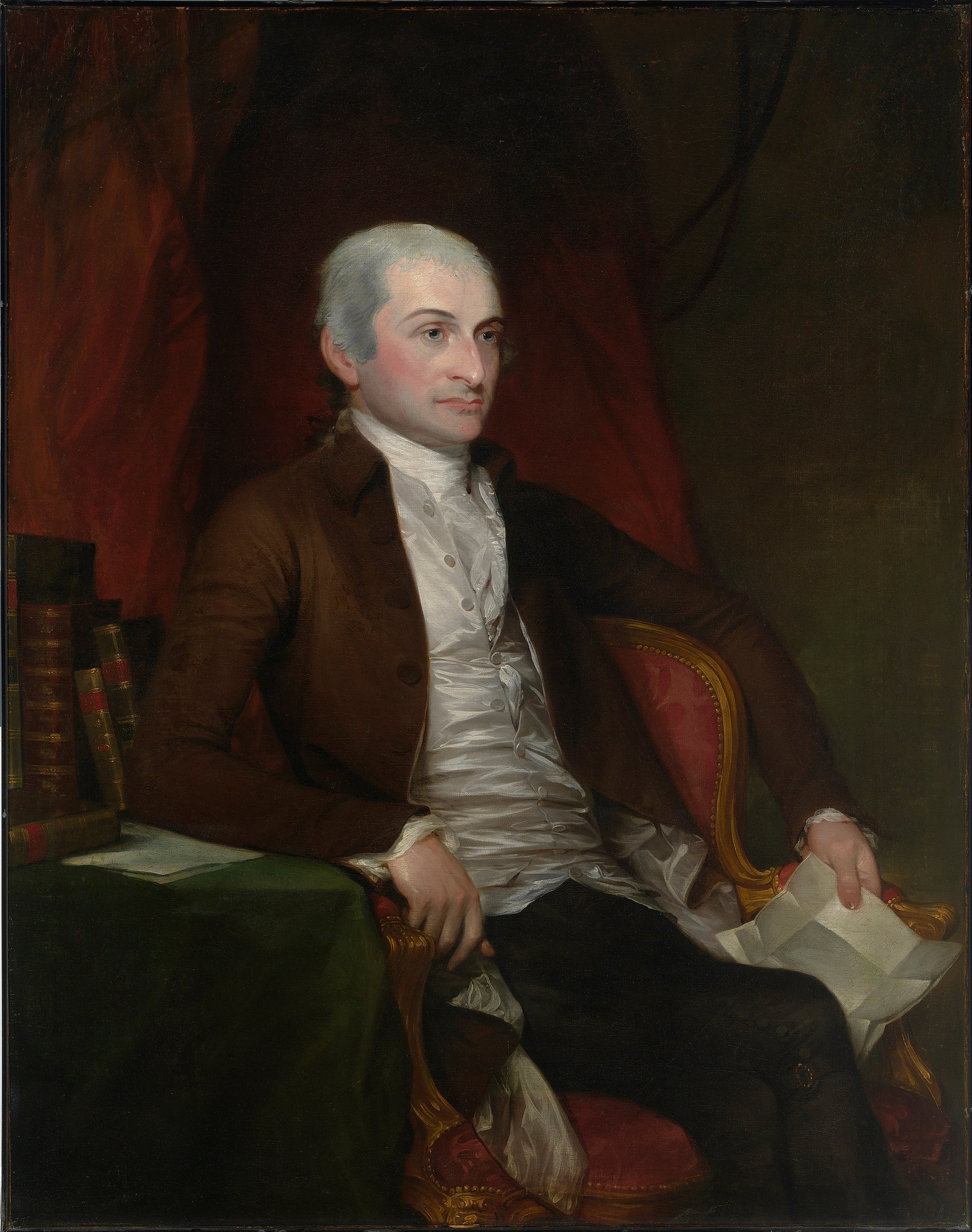

John Jay

1745 – 1829

Alexander Hamilton

1757 – 1804

John Jay and Alexander Hamilton were both New York lawyers, statesmen and ardent patriots whose shared conceptions of liberty and good governance sparked a friendship and kept them in close contact through decades of public service. But in character, they were as sharp a contrast as could be.

John Jay and Alexander Hamilton: The Greatest Columbian? You decide…

Face to face across Columbia’s southeastern quad stand two buildings whose names affirm this College’s boast at having launched two great architects of America’s independence.

John Jay and Alexander Hamilton were both New York lawyers, statesmen and ardent patriots whose shared conceptions of liberty and good governance sparked a friendship and kept them in close contact through decades of public service. But in character, they were as sharp a contrast as could be.

Hamilton tends to be the better known today. His handsome countenance commands the ten-dollar bill nationwide, and on campus the dashing statue guarding Hamilton Hall gives him face time every day. Known for rapid-fire thought and zest for action, he could write and recite poetry at the drop of a hat, and thrilled to the scent of battle. Picked by Washington as an aide-de-camp, he became one of the General’s closest, life-long confidantes, friends and advisors.

After the war Hamilton argued vociferously for the federal Constitution, and then laid a foundation for the nation’s financial system as first Secretary of the Treasury. Yet for all his heroic dash and talent, a restless discontent and lack of self-control also ruled in Hamilton’s life. They mercilessly consumed his energies, tarnished his reputation with adultery, and ultimately cost him his life in a needless duel. And [in May 2004], when the Columbia Spectator released their choice for the number one alum of all time, it was Jay, not Hamilton, who rightfully stood atop that list of two hundred-fifty names.

Hamilton and Jay:

Fellow Columbians and fine founding fellows. Each poured vigor, patriotism and intellectual power into his respective offices, but who was really the greatest? Whose life would you emulate? To adjudicate this question requires a now unconventional set of standards....

While the decision surprised some, the Spectator in so choosing uncovered a jewel of a character, long obscured by both the politics of his day and Jay’s own self-deprecating manner.

It is Noemie Emery who records this word-portrait of Jay, found in the memoirs of his contemporary, Alexander Graydon. Paraphrasing, she paints in “the tall, lean body, the scholar’s stoop; the aquiline nose and deep black eyes; above all, the serenity of the genuinely devout.”

And then quoting the source directly: “His manner was very gentle and unassuming. His deportment was tranquil, and one who had not known him … would not have been led to suppose that he was in the presence of one eminently gifted with intellectual power…”

That “unassuming” aspect of his character marked Jay and set him apart from his peers. Declining a nomination for governor of New York in 1777, he made this characteristic statement:

“That the office of first magistrate of this State will be more respectable, as well as more lucrative, and consequentially more desirable than the place I now fill, is very apparent.

“But, sir, my object in the course of the present great contest neither has been, nor will be, either rank or money. I am persuaded that I can be more useful to the State in the office I now hold than in the one alluded to, and therefore think it my duty to continue in it.”

It wasn’t that Jay had an unnatural aversion to eminence or pleasure. His legal practice prior to the war had ranked among the most prominent in New York. The office he felt bound to continue in (at age 32) was Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court. And he was exceptionally happy in his marriage, regretting only the frequency with which duty took him away from his Sally and their children.

But the stakes in the American Revolution were, in his mind, of the highest order and this was no time for personal aggrandizement. He accepted promotions only after weighing the urgency of the need at hand. He sought no personal rewards. And when honors did come, he held them lightly, ready to let them go if higher priorities should present themselves.

In 1778 New York sent him to the Continental Congress. The Congress had little power then, and less money. Pursuit by the British, factions and frustrations all abounded. Yet when elected its president at the end of the year, he accepted, despite the extended separation from family that this would impose.

A year later he was appointed “Minister Plenipotentiary” to Spain. This lofty title boiled down to requesting money and diplomatic recognition from a powerful and opportunistic court. It entailed even further and more prolonged removal from New York. Leaving his ailing father for the last time he set sail for Spain in the fall of 1779. He was now 34.

With no bargaining chips, and not even a budget for his own living expenses, Jay’s position in negotiations was painful. For eighteen long months the Spaniards delighted themselves by dangling promises before him while pressing for rights to the Mississippi River and other concessions. It was a victory just to say no.

Jay took on these titles at such personal cost for two main reasons. First, he, more than most, comprehended both the risks and potential rewards at stake in America’s fragile undertakings.

His ancestors were Huguenots, French Protestants who had fled fierce Catholic persecution in late 17th century France. Jay grew up hearing stories of his great-grandfather’s harrowing escape as royalist troops moved in to destroy their hometown.

Speaking back in 1777 at the opening of the New York Supreme Court, he had described the freedoms that the new state constitution would protect:

“While you possess wisdom to discern and virtue to appoint men of worth and abilities to fill the offices of the State… your lives, your liberties, your property, will be at the disposal only of your Creator and yourselves. You will know no power but such as you will create; no authority unless derived from your grant; no laws but such as acquire all their obligation from your consent.”

These precious American liberties had afforded refuge and life for his family. But they would only continue if America prevailed in the war. But there was a second, deeper reason for Jay’s self-sacrifice. Graydon concluded his portrait by describing Jay as one who “thought and acted under the conviction that there is an accountability far more serious than any which men can have to their fellowmen.”

This sense of accountability used to be called the “fear of God” —a conscious reverence towards the Creator who holds his creatures to account. The conviction that such a reckoning lay ahead disposed Jay to apply sober care and prudence to all he did and said.

At the same time, he drew great comfort from his Biblical understanding that God was good, and graciously provided for those who put their trust in Him. “If men would never forget that the world was under the guidance of a Providence which never erred,” he often remarked, “it would save much useless anxiety, and prevent a great many mistakes.”

This blend of caution in conduct and confidence before God enabled Jay to maintain a sober and serene temperament even in the midst of great trial. Add to this his capacities of reason, expression, and sound judgment and it was no surprise that ever greater responsibilities sought him out.

This blend of caution in conduct and confidence before God enabled Jay to maintain a sober and serene temperament even in the midst of great trial.

In 1782, with no sign that the Spanish intransigence would ever soften, Congress sent Jay to join Ben Franklin and John Adams in Paris for peace negotiations with Britain. Here his lessons in European-style_ diplomacy, so painfully acquired in Spain, began to pay off.

At a key juncture, Adams was delayed in Holland and Franklin fell ill— Jay became the principal negotiator. He rose to the occasion and Adams, who admittedly thought little of Franklin, later gave Jay “principal merit” for the Treaty of Paris that they finally concluded.

At 38, Jay had already lived a full public life, and returning home in 1783, he had every intention of resuming life as a private citizen. Congress, however, had other ideas and within three months had appointed him Minister of Foreign Affairs. He accepted, and became the leading officer of the new national government in New York City. Here he took on the role of a quasi-Prime Minister, directing affairs among the states as well as with foreign nations.

Under the Articles of Confederation, however, severe restrictions had been placed on that government’s power and Jay became increasingly frustrated at his inability to effect needed policies. Late in his term he joined Hamilton and others in advocating a stronger national government under a new federal Constitution.

In 1789, under that newly ratified document, Washington appointed Jay the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He was just 44.

As the President put it, Jay, more than any other possessed “the talents, knowledge and integrity which are so necessary to be exercised at the head of that department which must be considered as the keystone of our political fabric.”

Jay served as Chief Justice until 1795, when, on returning from a difficult diplomatic mission to England, he was elected Governor of New York in absentia. Retiring from the Court, he served two terms of office during which he signed the law that would lead to the abolition of slavery in the state, a cause he strongly supported.

Finally, in 1800, now President Adams re-nominated Jay for Chief Justice, stating that “It appeared to me that Providence had thrown in my way an opportunity of marking to the public the spot where, in my opinion, the greatest mass of worth remained collected in one individual.”

Jay, however, declined. He had done his duty and desired only to enjoy “the sweets of undisturbed retirement” with his beloved Sally. Asked how he would now occupy his time, he replied with a smile, “I have a long life to look back upon, and eternity to look forward to.”

Sources:

Emery, Noemie. Alexander Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, NY. 1982.

Jay, William. The Life of John Jay. American Foundations Publications. Bridgewater, VA. 2000. v. 1.

Smith, Donald L. John Jay: Founder of a State and Nation. Teachers College Press, NY. 1968.

Pellew, George. John Jay. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1890.

Whitelock, William. The Life and Times of John Jay. Dodd, Mead, NY. 1887.