Evolution: Could Random Forces Have Invented the Marvelous Eye?

Her evolutionary biology class made her so unhappy, my friend said. The professor decided to lecture not just science, but attitude, too. For two lectures, she jabbed at the very idea of a creator, sneering at those who would embrace one. The podium was hers, and my friend, one among a hundred listening, could do little more than sit uncomfortably and hope for the end.

I, too, remember being frustrated in biochemistry when evolutionary principles would be called on, uncontested, to explain life processes. It bothered me enough that one day, I called up the courage to ask the professor outright, “Why?” Why have biologists placed evolution among the inviolable truths of life? As I understand it, it is still unproven theory. Why wasn’t it presented as theory? One sentence to this point would have at least been fair. I can’t remember what the professor exactly replied, but it wasn’t satisfying.

As teachers of science, it is only reasonable for professors to present things as precisely as possible. To present evolution as fact, not theory, is no small shift of emphasis; that shift could alter one’s whole world view.

Naturalistic Macro-Evolution

I refer here to one narrow strain of evolution, which Darwin first offered to the world in Origin of Species in 1859, naturalistic macro-evolution.

Naturalistic macro-evolution holds that impersonal forces driven by chance are responsible for the inception of life and the diversity of life on Earth today, including you and me. It explains all life without the aid of any intelligent power beyond the scope of the material universe. At its purest, it allows nothing outside the material realm: everything comes from natural processes occurring according to observable, physical laws. At most, it concedes that if God exists, he doesn’t matter one bit to us.

This particularly is what I mean by “evolution.” To begin to broach all the hybrid theories of “guided macro-evolution” would open fields of debate this essay is not intended to cover. Though perhaps a narrow definition, naturalistic macro-evolution has the profoundest impact today, not the least because most biology professors subscribe to it today, and many, many students accept it wholesale.

People more qualified than I have written books detailing problems with naturalistic macro-evolution, such as its mathematical improbability, or the incredible gaps in the fossil record. A fleshed out discussion could easily fill several tomes. I do not pretend to have the definitive word on the topic. For any objection I have, an evolutionist can think of some response, and then a non-evolutionist may answer the response, and so forth.

As with anything beyond our present grasp, whether be it metaphysical or simply outside the reach of scientific tools, the human mind can jockey justifications for its beliefs forever. Nevertheless, I do have a few thoughts to express.

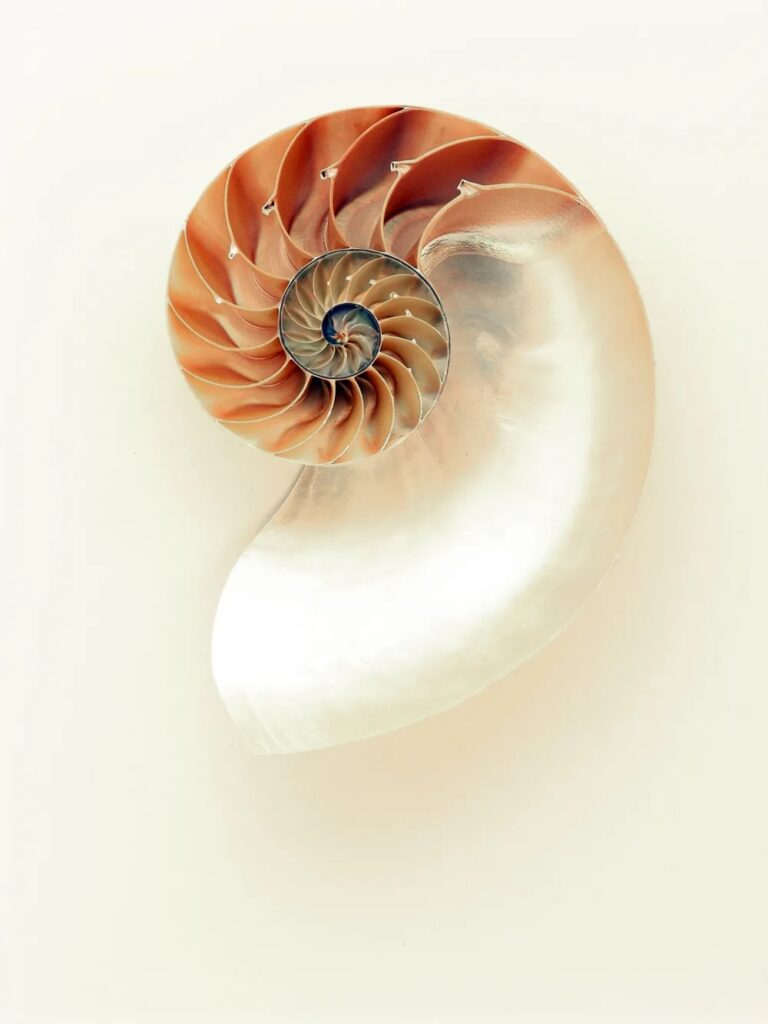

As the Nautilus grows and matures, it secretes a new chamber towards the open end of its shell and seals off the old section with a wall called a septum, resulting in a whole new physiology of buoyancy and mobility.

Mutations

For naturalistic macro-evolution, mutations are bedrock. Darwin’s theory on a large scale is that thousands and millions of small changes in genes each conferred the slightest bit of advantage to organisms, so they flourished and eventually become a new species altogether. Over millions of years, according to current thought, a reptile began to take on mammalian characteristics, such as hair, and warm-bloodedness, and live-birth of offspring, and eventually became what we now know as a mammal. The changes had to be tiny steps, or else it would not be evolution.

If a mouse were born from a snake egg, that would be closer to creation by divine intervention than evolution. Or even on a level lower, if a chameleon were to give birth to little chameleons having a feathered wing, that too would be more miracle than Darwinian evolution.

But how then, does a tiny change give advantage? Does one-half percent of a wing help or hinder? If a chameleon’s leg were to become slightly wing-like, wouldn’t it be hindered from scurrying across the sand, and climbing up bushes, actually making it more vulnerable?

Or as the famous evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould once asked healthily, “What good is five percent of an eye?” Some have answered that five percent of an eye is good for five percent sight. But five percent of a physical eyeball does not give you five percent sight. To have any sight

requires, in addition to the physical eye, vision processing equipment neurons for intake of outside stimulus, and neurons to process the signals. Did all these areas of the organism mutate slightly by chance, at the same time and in the same direction, millions and millions of times to become the magnificently remarkable and complex eye we have today?

Another issue is raised when we consider the nautilus, a sea creature that in hundreds of millions of years of existence has yet to develop a lens for its retina, which according to the eminent evolutionist Richard Dawkins, it cries out for. If the mutational mechanism is powerful enough over Earth’s history to form the amazing human eye and many other eyes (some Darwinists agree there are at least forty evolutionary lines for the eye), why couldn’t it form a single lens on a nautilus in all that time?

Fossil Record

If mutational theory is evolution’s bedrock, the fossil record is its banner. Everyone has seen artist depictions of a pre-human human based on a fragment of some hundred thousand-year-old skull. Everyone has seen the imprint of the Archaeopteryx, half-reptile, half-bird, with its neck forever wrenched backward. And there are others here and there that look to be “between” species. Darwinism posits innumerable transitionals that have since died out, replaced by more complex variants of itself.

In relation to the fossil record, Darwinism stands or falls on whether the fossils representing vast periods of time reveal thousands and thousands of transitionals. Darwin said himself, “The number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great.”

But a close look at the record to date shows convincingly that “between” species are exceptions rather than rules, though the exceptions receive all the press coverage, in textbooks, in newspapers, in the classrooms, and in the papers of paleontologists. Where are the transitionals?

They should be everywhere. Given the estimated 10 million species on earth (with assuredly thousands in the depths of the seas and the earth as yet unknown), having evolved through time from a single bacteria, and the 130 years of fossil hunting since the Origin of Species came out, transitionals should be so numerous, that single fossils such as the Archaeopteryx really shouldn’t attract such focused attention.

And who has yet explained the “Cambrian explosion,” the appearance of nearly all the animal phyla 600 million years ago without any adequate evolutionary precedents? In fact, the fossil record spoke so resolutely against gradual development that some Darwinists in the 1970’s developed an adjunct theory called “punctuated equilibrium” to explain it, saying only the margins of a population change to become a new species (which is why transitionals do not show up in the fossil records), after which it rejoins at once the former population.

The well-known evolutionist Gould and a colleague authored the theory because, in his own words, “The history of most fossil species includes two features particularly inconsistent with gradualism: 1. Stasis (of species)… 2. Sudden appearance (of species).” I will only say here that punctuated equilibrium is controversial among biologists.

The Intelligence Of It All

If we step back and consider the millions of processes that support a self-sustained organism in perfect concert, with eyesight and all the interconnections and capacities in the brain that accompany it, with hearing and everything that accompanies it, with smell, with digestive abilities, with muscular contraction and expansion, with excretory abilities, it is hard not to notice the intelligence of it all.

Everything works so smoothly together to let a monkey jump from tree to tree, and to make a pianist run his fingers across a keyboard and bring out a sonata. Even yet, for an amoeba to swallow a paramecium, or a single bacteria to sustain itself, tens of thousands of processes must work together. Was all this intelligent complexity ground out by impersonal forces over time? Do the laws of nature hold some hidden genius to effect something so incredible as a living organism?

We can ponder genes and DNA for hours, and never get over how marvelous the system is. It is mind-boggling to think of all the proteins shaped according to genetic information, with the perfect mix of van der Waals forces and electrostatic attractions to twist around into that perfect shape to become things that combine into mitochondria and other organelles, and regulate materials that pass between sections of the cell, and even help the DNA, its creator, to replicate, or form other proteins.

Any cell biologist will tell you that a single cell in your body can be as complex as New York City on New Year’s Eve. If you focus your microscope onto a cell and observe, you find mitochondria working to churn out ATP, and organelles of odd sorts and shapes swimming in various directions all to the beat of life. And for everything visible, there are thousands of molecular interactions invisible.

How could intelligence arise out of chaos? Robots show an intelligence. They can be programmed to put doors on car chassis, or bring medicine down a hospital hallway to patients. They can show intelligence because they have an intelligent engineer that created it.

The most complex of robots are nothing next to the layers of complexity of the simplest life system. Can the genius of genetic coding not have a mind behind it? The famous cosmologist, Sir Fred Hoyle, once said that the first living organism emerging by chance from a chaotic mix of chemicals is as likely as “a tornado sweeping through a junkyard might assemble a Boeing 747 from the materials therein.”

Conclusion

Darwin was just a man, like you and me. Certainly, he owned a keen intellect, but he wasn’t a super-man. Observing animal life on the Galapagos, he began to formulate a theory of how things became the way they are. He conjectured, scratched out lines of thought, tried to fill in gaps by using logic and imagination, without performing one empirical test—he did it all by deduction. This is the scientific way.

But like you and me, he was capable of error, of stretching too far on a certain point. And like our judgements, his should be open to honest criticism. Darwinism is a scientific theory, an extremely elegant one, but nevertheless a theory that should be treated as such. It is a little strange to me why it has achieved the status of the sacred, why high school teachers give it out as grade school teachers do the multiplication table, and college professors find it appropriate to express emotional hostility to those that oppose it, namely, those who believe in a divine Maker.

Besides, for all the apparent logic in Darwinism, what’s really more logical, that I, with my body, with all my emotions and mental capabilities, with all my longings for God, arose from a bacteria, or that God shaped me with His hands?

Taejoon Ahn, Jonathan Edwards ’96

(Much debt is owed to Philip Johnson’s Darwin on Trial, Regnery Gateway, Washington, D.C., 1991.)