The Long Difficult Birthing

The planters “cast [themselves] into several private meetings wherein they that dwelt nearest together gave their accounts to one another of God’s gracious work upon them and prayed together and conferred to their mutual edification . . . .” With 14 months of such prayer and fellowship they laid a solid foundation for the colony.

The Long Difficult Birthing

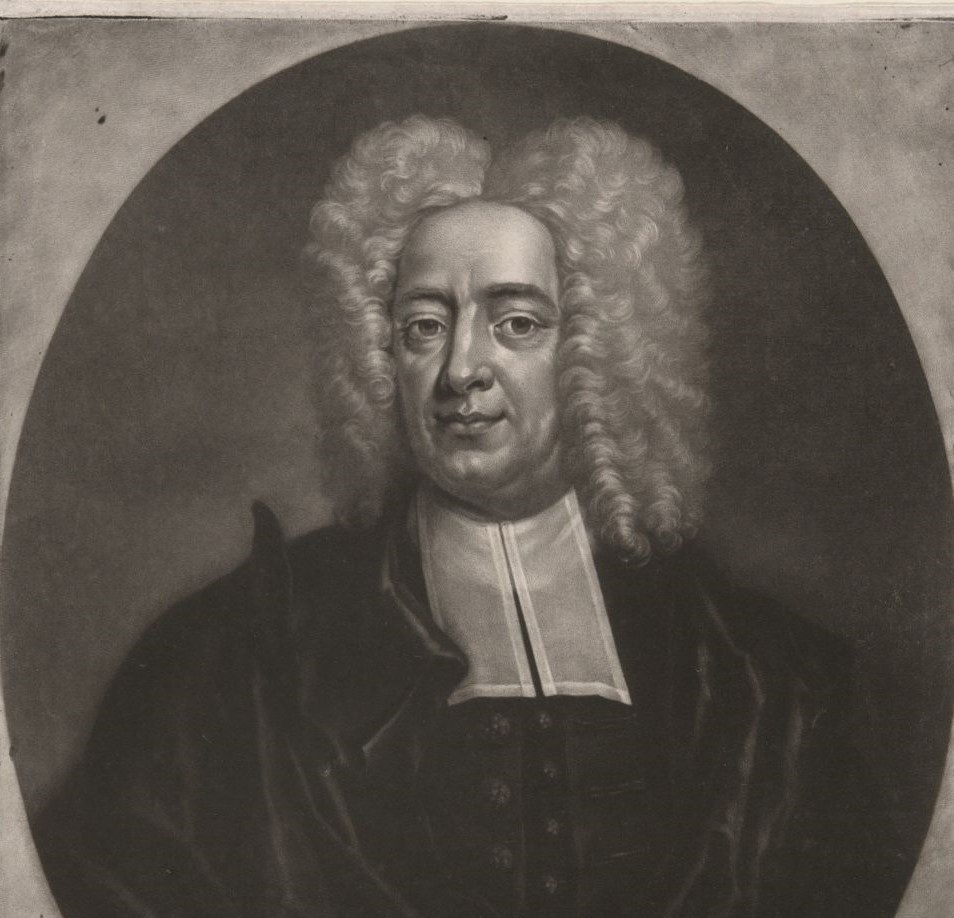

In 1665 the New Haven Colony was collapsing. Of all the New England settlements, it had been the most steadfastly Biblical. A company of Englishmen led by London minister John Davenport and London merchant Theophilus Eaton had established the colony in 1638/39, intending to “drive things in the first essay as near to the precept and pattern of the Scripture as they could be driven.”

The colony records show what kind of plantation these New Haven pioneers hoped to have. Before they began either church or civil government, the planters “cast [themselves] into several private meetings wherein they that dwelt nearest together gave their accounts to one another of God’s gracious work upon them and prayed together and conferred to their mutual edification . . .” With 14 months of such prayer and fellowship they laid a solid foundation for the colony.

But by 1660, the outlook was bad for Puritan New England. The Stuart dynasty, whose oppressions the Puritans had fled, was restored to power in England. Charles II was now on the throne, and the Bible commonwealth of New Haven hardly stood in his best graces. Then, in 1662, neighboring Connecticut Colony obtained a royal charter granting it jurisdiction over the whole of the New Haven Colony. John Davenport and others resisted absorption by the larger colony, but by 1664, New Haven’s options were limited. It was either assimilate with Puritan Connecticut or accept hostile takeover by Anglican New York.

But even assimilation with Connecticut (the course New Haven Colony chose) meant the surrender of a critical part of New Haven’s Biblical stand. Connecticut favored the so-called “Halfway Covenant” by which baptized, though unconverted, persons were allowed to present their children for baptism. Davenport rightly insisted that this spelled destruction for the church for which the New Haveners had aimed, the Scriptural church composed of true believers.

Not everyone accepted the new order of things. By 1666, many New Haven Colony stalwarts had left to establish a new Biblical plantation in what was to become Newark, New Jersey. In 1668, John Davenport himself returned to Boston, where the New Haven enterprise had been born. He could not have imagined, as historians would later trace it, that his life was inseparable from the founding of a college that he never saw.

A college was needed, not simply to train ministers, but, as Davenport said, “To fit youth . . . for the service of God in church and commonwealth.”

A college was needed, not simply to train ministers, but, as Davenport said, “To fit youth . . . for the service of God in church and commonwealth.”

John Davenport

Davenport’s Collegiate School

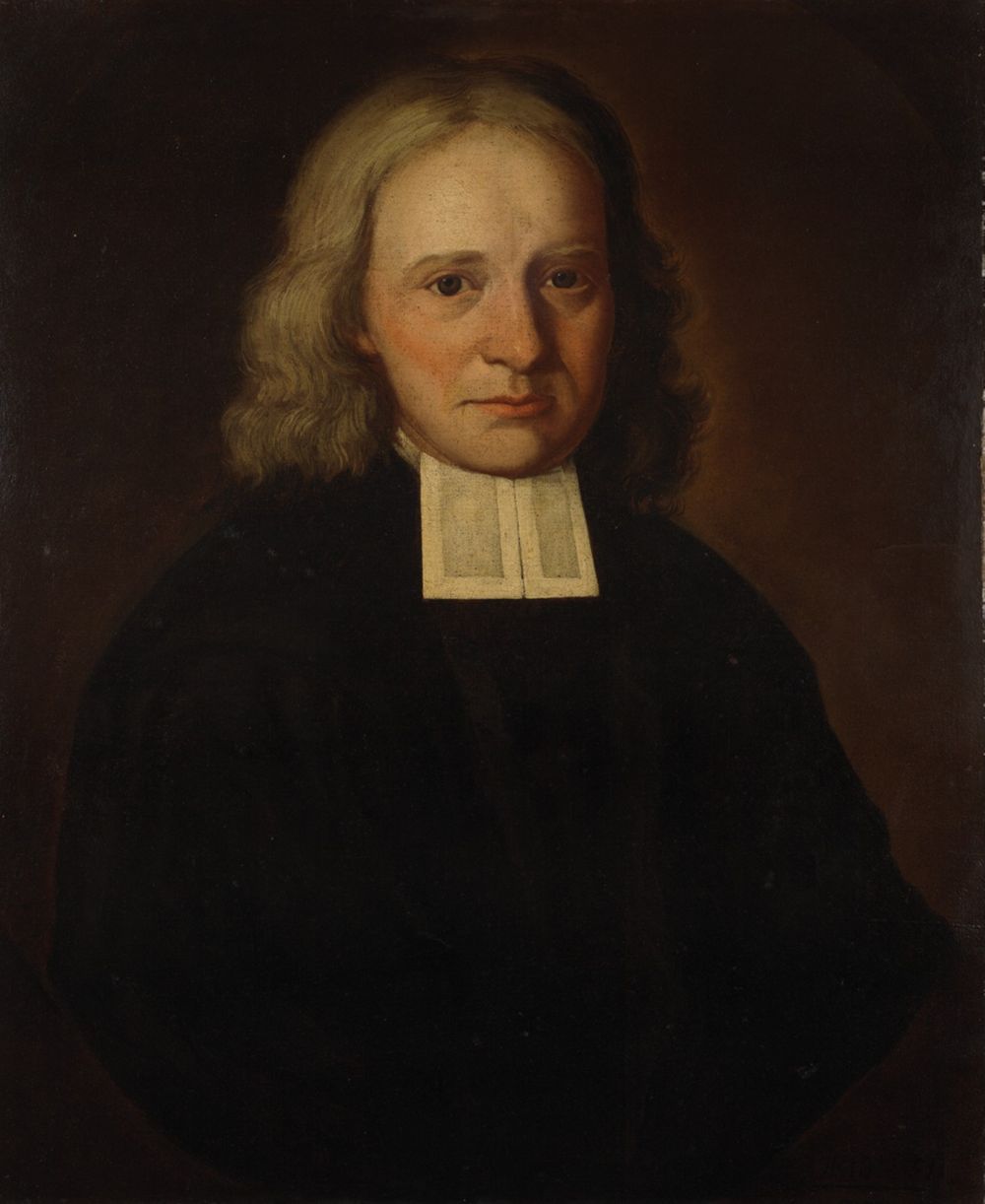

Abraham Pierson, Sr., Missionary

Others wanted to trade with the Indians, but Pierson, in his own words, wanted “to treat with them concerning the things of their peace.” In visiting the tribes in this work, he is known to have traveled as much as 800 miles a month. He learned the language of the Quinnipiac Indians and gave them the only work printed in their language, a catechism called Some Helps for the Indians (1660). He also undertook the education of the son of the official native interpreter, who had failed at Harvard. Some of the native converts of Pierson’s ministry served as interpreters in the legislative assembly in New Haven.

New Haven Colony records show at least 21 years’ effort on Davenport’s part toward the college. He attempted to found a grammar school, as a kind of preliminary step. (Grammar schools were the college prep schools of the day, in that they instructed students in the classics.)

Only ten years after the colony’s founding the legislative assembly formed a committee to consider what vacant lot to reserve for a college “which they dissire maye bee sett up so soone as their abillite will reach therunto.” The receptivity of the colony to the college plan went up and down with the years, but Davenport seized every opportunity to encourage a beginning.

For a while, little more was done, but in 1654/55, at the urging of Davenport and others, colony towns pledged considerable money to the effort, and the birth of a college seemed certain. Happy at this movement, Davenport wrote to wealthy Edward Hopkins in London, hoping to interest him in the work. Hopkins, who had served as governor in the Connecticut Colony, was New Haven Governor Theophilus Eaton’s stepson-in-law, and looked on Davenport as a father in Christ. He reported to Davenport, “That which the Lord hath given mee [in New England], I ever designed the greatest part of it, for the furthering of the work of Christ in those ends of Earth.” He promised to provide support for a college once it was actually set up, and shaped his will accordingly.

Upon Hopkins’ death in 1657, Davenport became a trustee of his estate. Though the 1650s plans for the college imploded when the wife of the school’s prospective president objected to his undertaking the task, New Haven’s sturdy minister did not give up. In 1660, he delivered to the governor and magistrates of the colony a copy of Hopkins’ will and an inventory of his estate in New England. He urged them to begin a grammar school at least, in order to qualify for Hopkins’ legacy. Davenport pointed out that income from a town oyster shell field could defray the expenses of a grammar school and college, and suggested they donate the lot the New Haven library now stands on as a site for a college.

He pled with the elders and magistrates that they “not suffer this [Hopkins’] gift to be lost from the Colony, but as it becometh Fathers of the Commonwealth, will use all good endeavors to get it into their hands, and to assert their right in it for the common good, that posterity may reap the good fruit of their labours, and wisdom, and faithfulness.”

However, lose the gift the colony almost did. The grammar school they began in 1660 failed because neither students nor parents were serious about the undertaking, and in 1662 the colony voted to abandon the project. A series of abortive attempts to revive it followed. Finally, in 1667, after Connecticut had absorbed the New Haven Colony, and Davenport had again pointed out that the Hopkins bequest stood to be lost, the town of New Haven opened a grammar school with a self-perpetuating board of trustees to whom Davenport, as Hopkins’ trustee, could assign New Haven’s portion of his legacy.

Though this grammar school sometimes referred to itself as “the Collegiate School” or “college,” it never became one. The college portion of Hopkins’ bequest, though intended for New Haven, was finally awarded long after Davenport’s death to Harvard.

In 1665, when the New Haven Colony fell apart, Davenport had written to a friend in Boston that “Christ’s interest” in New Haven was “miserably lost.” As one scholar of the period notes, the suppression of the colony (and, it might be added, the failure of the college plan) “represented the depth of human tragedy—the plans and efforts of a lifetime came to naught.” At almost 70, Davenport felt too old to begin again, as others did, in New Jersey; it was actually Abraham Pierson who led the Newark enterprise.

But Davenport had long demonstrated faith in something besides his own efforts. On first hearing of the Stuart restoration, which boded so much trouble for New England, Davenport had written to Connecticut Governor John Winthrop Jr., “Our comfort is, that the Lord reigneth, and his counsels shall stand.” And so it proved: even Davenport’s failures were not in vain.

Thirty-one years after his death in 1670, the college he had so long, so dearly envisioned came to be.

Rebirth: James Pierpont and the founders of Yale

Hopkins School in New Haven still stands as testament to John Davenport’s struggle for a college, yet it also speaks of his frustration. Still, the rest of his larger plan, apparently moot, was destined to bear fruit at last.

In 1701, a group of Connecticut shoreline clergymen, led by New Haven’s James Pierpont, wrote a series of letters to respected New England lawyers and ministers, asking advice on how best to go about forming a college. The story of Yale’s founding as it is usually told begins here. But there is a little-known and surprising background to this college initiative which tells us a great deal about the motives behind Yale’s establishment.

Young Harvard graduate James Pierpont came to New Haven in 1685 and entered into John Davenport’s old pastorate. Not only this, but he boarded at the home of Abigail Davenport, widow of John Davenport, Jr., son of New Haven’s earliest minister. Six years later, Pierpont married Abigail’s daughter, also named Abigail. The bride died of consumption not long after the wedding, but the cords that tied Pierpont’s heart to the Davenport family were not severed there.

The New Haven town records contained an entry which notes James Pierpont’s purchase of about 100 books, originally in the possession of John Davenport and given to him by Theophilus Eaton, specifically for the planned New Haven college. The books came from the library of Samuel Eaton, Theophilus’ brother, and were passed to Davenport in 1656, when the establishment of a college looked like a virtual certainty.

We have no James Pierpont diaries, no detailed record of how he arrived at the determination to begin a college. But around 1898, local historian Henry Blake stumbled on a previously unknown entry in the New Haven town records for 1689—a window upon James Pierpont’s intentions.

The entry notes James Pierpont’s purchase of about 100 books, originally in the possession of John Davenport and given to him by Theophilus Eaton, specifically for the planned New Haven college. The books came from the library of Samuel Eaton, Theophilus’ brother, and were passed to Davenport in 1656, when the establishment of a college looked like a virtual certainty.

Because they were intended for a college, the books were left by Davenport to the town, but were stored at Abigail Davenport’s house, just where Pierpont boarded when he first came to New Haven. Pierpont bought Davenport’s beginning of a college library, for “40 bushell Rye and 32 bush. indian corn,” apparently to rescue it for the purpose for which it was originally intended. He had caught the vision Davenport had carried, the vision of a college designed to equip youth for service to God in every sphere of life.

Besides Pierpont, several other ministers who helped realize the vision for the college had direct links to John Davenport and his collegiate school. Noadiah Russel, classmate of Pierpont at Harvard, was a student pledged to matriculate at the New Haven grammar school in 1667, when Davenport got it started again after its lapse in 1662. Samuel Russel was a classmate and friend of Pierpont at college, and his father had been an associate of John Davenport. Samuel himself had been master of a school started by a portion of Hopkins’ bequest. Israel Chauncy, the oldest of Yale’s founders, had been a religious ally and protégé of Davenport. Chauncy had been invited in 1664 to conduct the Hopkins Grammar School, but funds had been too low to support a master.

The founding ministers were linked not only to Davenport, but also to Davenport’s partner, Puritan missionary Abraham Pierson. When Pierpont married Abigail Davenport the younger, he married not only into the Davenport family, but also into the Pierson family. His new mother-in-law Abigail was Abraham Pierson, Sr.’s “choice and precious daughter,” [Pierson’s words] so Pierpont had married Abraham Pierson, Sr.’s granddaughter and Abraham Pierson, Jr.’s niece.

Abraham Pierson, Jr. was not simply a founding minister, but as hardly bears mentioning at Yale, the college’s first rector. When asked to be Rector, he said he “durst not refuse this service to God and his generation.”

The closeness of the founders and their partnership together in the Gospel is reflected in their family relationships. Not only did many of them marry into each other’s families, but many of their children intermarried.

By now it should be plain that Yale’s founders remembered and cherished the spiritual vision and burden their fathers bore. More critically, they were determined to bring this Gospel vision to reality. The first generation’s labors had not been in vain, for a seed was planted in the hearts of their physical and spiritual children.

Abraham Pierson, Jr. was not simply a founding minister, but as hardly bears mentioning at Yale, the college’s first rector. When asked to be Rector, he said he “durst not refuse this service to God and his generation.” . . . By now it should be plain that Yale’s founders remembered and cherished the spiritual vision and burden their fathers bore. More critically, they were determined to bring this Gospel vision to reality. The first generation’s labors had not been in vain, for a seed was planted in the hearts of their physical and spiritual children.

Two concrete witnesses to these facts still remain in Yale’s libraries and archives. First, the books bear witness, both the books the founders themselves gave, and the books which Eaton and Davenport gave long before. Each costly volume represents a sacrifice little understood by our generation. Going by the list of known titles, and by autographs and inscriptions in the books themselves, we can say Yale today has at least 13 volumes from James Pierpont, 11 from Israel Chauncy, between 17 and 21 from Abraham Pierson, Jr., and a handful from the other founders. Not only this, there are almost certainly 45 to 50 volumes from Eaton and Davenport themselves, a remnant of the library James Pierpont recovered from New Haven for 72 bushels of grain. Some of the books are even inscribed “given to the J.D. [John Davenport] Collegiate School.”

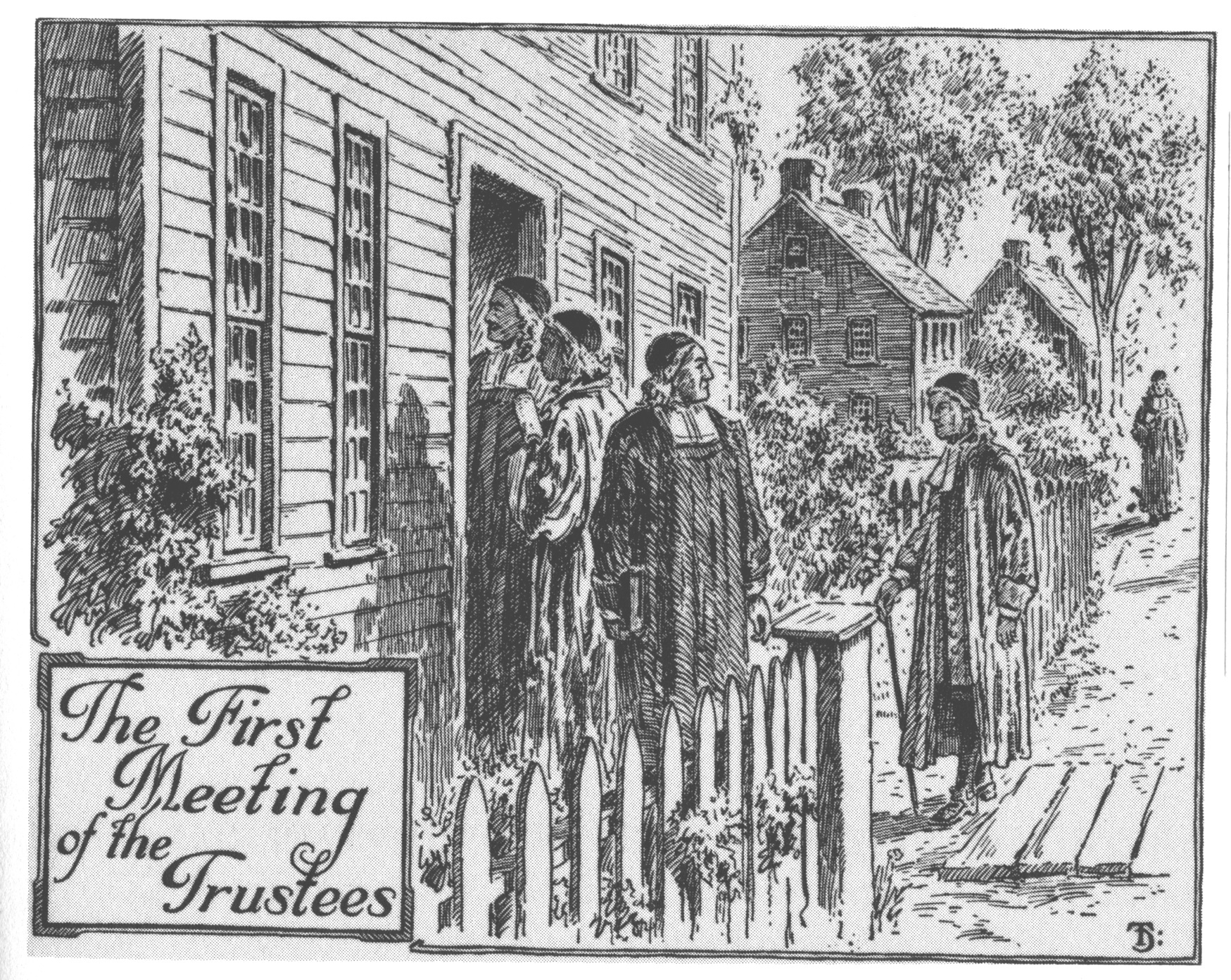

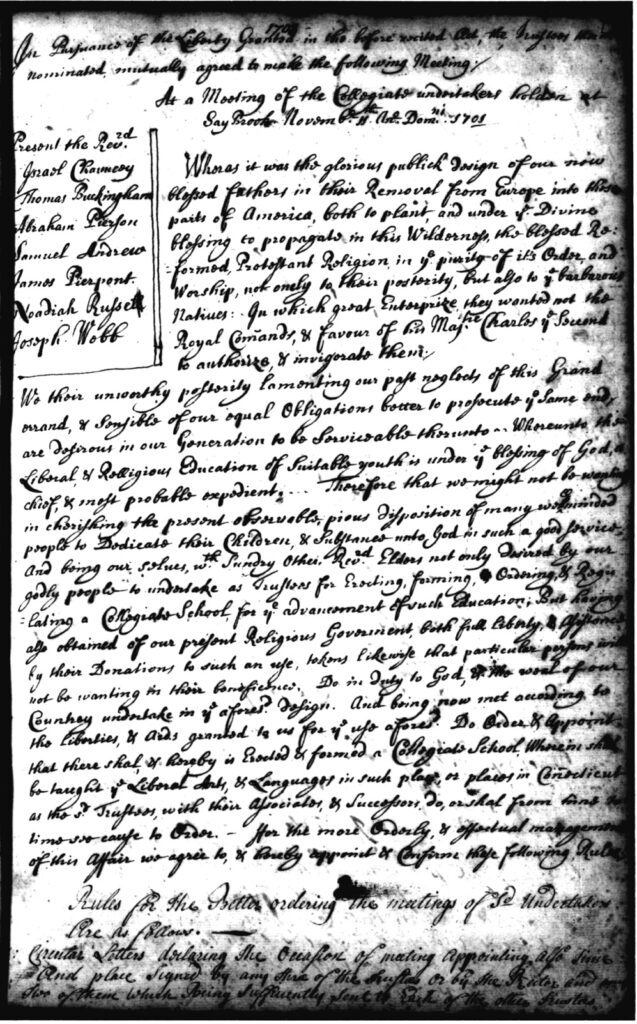

The second testimony that the founders were their fathers’ spiritual children is in Yale’s founding documents, in the charter granted by the General Assembly in October 1701, and the proceedings of the first trustees’ meeting in November 1701.

The charter states that liberty to erect a “collegiate school” is given to trustees that “Youth may be instructed in the Arts & Sciences who thorough the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for Publick employment both in Church & Civil State.” The charter echoes Davenport’s own stated purpose for founding a college.

More poignantly, the trustees or founding ministers noted in their proceedings of November 1, 1701, that it was “the glorious publick design of [our] now blessed fathers “both to plant, and under the Divine Blessing to propagate” in America the pure worship of God, not only to their posterity, but also to America’s native peoples. The trustees specify their desire to share in this Gospel purpose: “We their unworthy posterity lamenting our past neglects of this grand errand & sensible of our equal obligations better to prosecute the same end, are desirous in our generation to be serviceable thereunto—whereunto the liberal, & religious education of suitable youth is under the blessing of God a chief & most probable expedient.”

The trustees or founding ministers noted in their proceedings of November 1, 1701, that it was “the glorious publick design of [our] now blessed fathers “both to plant, and under the Divine Blessing to propagate” in America the pure worship of God, not only to their posterity, but also to America’s native peoples. The trustees specify their desire to share in this Gospel purpose: “We their unworthy posterity lamenting our past neglects of this grand errand & sensible of our equal obligations better to prosecute the same end, are desirous in our generation to be serviceable thereunto—whereunto the liberal, & religious education of suitable youth is under the blessing of God a chief & most probable expedient.”

Archaisms aside, their statement of purpose lets us see into the founders’ hearts. The previous generation had labored that the Gospel take root in this continent; Yale’s founders took up that labor, and their missionary vision, too. The Gospel must reach beyond their own children, to all for whom Christ died.

In view of both generations’ history, what shines through is not so much the faithfulness of men, but that of the God they served. He did not, as the Scriptures say He will not, forget the “work and labor of love” which they had “shown toward His name” (Hebrews 6:10). Yale’s founders experienced in their own lives the meaning of Jesus’ words “other men labored, and ye are entered into their labors” (John 4:38). We benefit today from the labor of love undertaken by both generations.

Marena Fisher, Graduate ’92

Mathers

Yale’s founding ministers wrote to godly Massachusetts divines Increase and Cotton Mather for advice on how to start a college. If anyone knew how to proceed, the Mathers did, having nurtured and watched over Harvard for years. Increase had been the college’s President since 1685.

Two Mathers of Yale Fact

When Yale’s founding ministers wrote letters to New England elders asking advice on how to start a college, they naturally wrote to godly Massachusetts divines Increase and Cotton Mather. If anyone knew how to proceed, the Mathers did, having nurtured and watched over Harvard for years. Increase had been the college’s President since 1685.

However, in June 1701, Harvard’s overseers took advantage of a technicality to sack Mather from the Presidency. Unitarianism and rationalism had laid hold of many of those in control of the school, and they were looking for a way to get rid of their Gospel-minded President. Mather left office September 6, 1701; nine days later he was writing a letter of advice to some Connecticut ministers very determined to start a college which would hold to Biblical truth.

Years after, Cotton Mather aided Yale when trustee strife over its location and a desperate lack of funds had almost sunk it. In 1718 he wrote to Elihu Yale, the wealthy ex-governor of Fort St. George in Madras, encouraging him to give a sizeable gift to the college that he might have a memorial to his name “better than a name of sons and daughters” and also better than “an Egyptian pyramid.” Elihu Yale gave much less than his wealth permitted, but his timely donation probably saved the school from collapse. It certainly put his name on it in perpetuity.

It is interesting to note that Elihu Yale was a descendant (by her first marriage) of Anne Eaton, Theophilus Eaton’s wife. His father, David Yale, had been raised in Theophilus Eaton’s household, but spent much of the rest of his life vindictively trying to destroy the civil and ecclesiastical structures of New England. As an Anglican, Elihu Yale was not all that favorably inclined to an “academy of dissenters.” But one wonders if God wasn’t moving in Mather’s faithful initiative.

Mather later wrote Gurdon Saltonstall, Governor of Connecticut and one of the original movers for the college, that it was to him “an unspeakable pleasure … that I have been in any measure capable of serving so precious a thing as your College at New Haven.”