When Moody Thrilled Yale

“Moody and Sankey, it is reported, will be in New Haven during the next moon. We hope that the Faculty will deem it advisable to omit a few recitations in order that the fruits of their coming may be enjoyed…by all without detriment to our temporal welfare.”

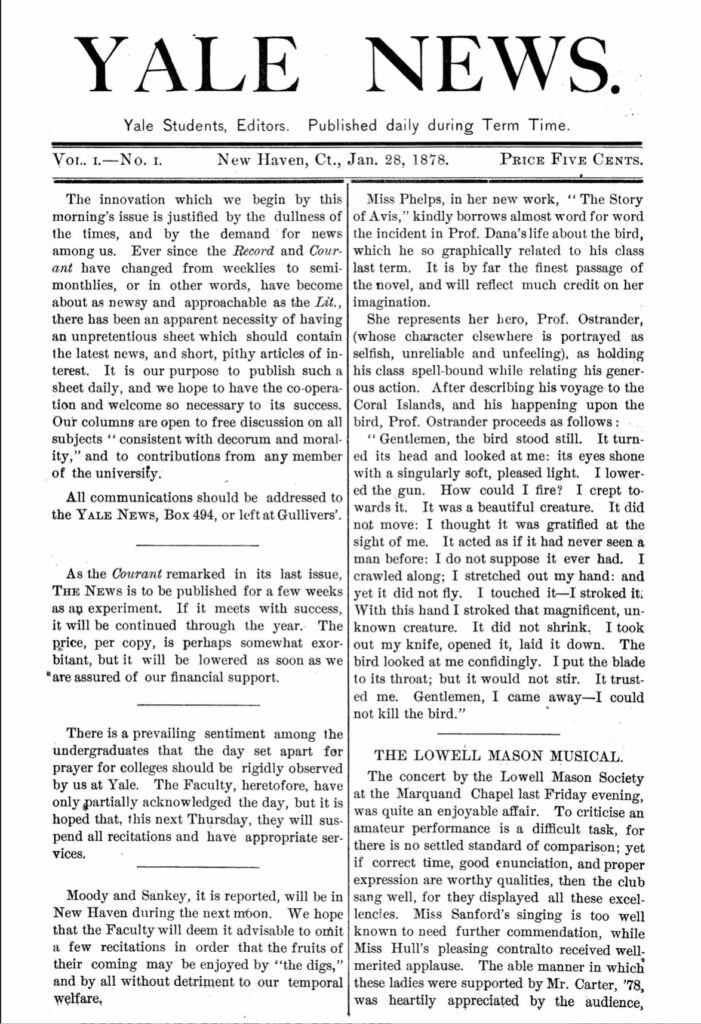

Moody & Sankey's Tabernacle

New Haven, Connecticut

On January 28, 1878, its first day of publication, the Yale Daily News carried on its front page the following student request:

“Moody and Sankey, it is reported, will be in New Haven during the next moon. We hope that the Faculty will deem it advisable to omit a few recitations in order that the fruits of their coming may be enjoyed…by all without detriment to our temporal welfare.”

Coming from Yale students, a request like this would raise an eyebrow or two today, for Dwight L. Moody and Ira Sankey were well-known revivalists, seeking to bring the gospel of Jesus Christ to New Haven. Moody was the Billy Graham of his era and Sankey its George Beverly Shea. Yet the college took full part in the effort to bring the evangelists to the area. The very same day the first issue of the Daily appeared, Yale President Noah Porter was downtown chairing a ministers’ conference with Moody over the details of the upcoming visit.

The labor undertaken to prepare for the gospel meetings would daunt a modern advance committee. Local businessmen and ministers decided New Haven didn’t have a hall large enough to handle the crowds the meetings would draw, and agreed to erect and pay for a building specifically for that purpose. The Tabernacle, as it was called, was put up in an empty lot at the crossing of Dwight and Whalley (about where the Rite Aid pharmacy now stands), and had a seating capacity of about 6,000. The builders were no slackers: construction began in early February and was finished by March 13, about ten days before Moody’s arrival.

Not to be caught unprepared, the Fair Haven and Westville Horse Railroad and other local railroads laid special switch track to the Tabernacle to accommodate the expected volume of travelers. A massive choir of 1300-1400 volunteers practiced for the meetings, and committees for ushers, ticket arrangement, and publicity were set up. A new hotel, restaurant, and livery stable were opened near the meeting site. Town prayer meetings for the campaign were held daily in the Center Church on the Green.

When Moody and Sankey arrived, the local response was immediate and overwhelming: people packed the Tabernacle for almost all meetings, though at least three were held each day for six weeks running. Churches had to be set aside to receive overflow crowds, and special meetings were held for young men, young women, and those with alcohol problems.

The message which drew the crowds was the simple report of the new life to be had in Jesus. At one of the early meetings, Moody said:

“‘Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.’ (John 3) I hope…every one [here] will be asking himself if he has been born again. We can’t afford to be deceived about this thing.…Ask a man if he is a Christian, and he will say ‘Yes, I go to church every Sabbath.’ So does Satan. He is busy here this afternoon. He’ll attend every meeting….Going to church ain’t being born again.…It isn’t a man trying to make himself better. It ain’t new associates. A man wants a new heart.” (New Haven Daily Palladium, April 1, 1878)

“‘Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.’ (John 3) I hope…every one [here] will be asking himself if he has been born again. We can’t afford to be deceived about this thing.…Ask a man if he is a Christian, and he will say ‘Yes, I go to church every Sabbath.’ So does Satan. He is busy here this afternoon. He’ll attend every meeting….Going to church ain’t being born again.…It isn’t a man trying to make himself better. It ain’t new associates. A man wants a new heart.”

New Haven Daily Palladium, April 1, 1878

Strangely enough, this gospel attracted all kinds of people. Converts included alcoholics, mechanics, carriage factory workers, a third baseman for the New Haven Haymakers baseball team, and the wealthy owner of the New Haven Clock Company.

Many Yalies had doubts that rough, uncultured Moody could have anything to say to a college man. One such was Reuben A. Torrey, then a senior in the Yale Divinity School. Torrey said:

“When Mr. Moody first came to New Haven we [students] thought we would go out and hear this strange, uneducated man. I…was about to take my B.D. degree. I knew more then than I will ever know in my life again. We thought we would patronize him a little bit. He did not seem at all honored by our presence, and as we heard that untutored man we thought ‘He may be uneducated, but he knows some things we don’t.’” Torrey’s attitude changed so much that later in the campaign, at one of the young men’s meetings, he gave public testimony to what Christ had done for him.

Clearly, others at Yale came to agree with Torrey. When Moody visited Battell Chapel on April 7, and again on April 16, some students repented and believed. Others reconsecrated themselves to God. On April 9 the New Haven Daily Palladium noted that one anxious Yale parent inquired after the spiritual state of his son, only to discover that he had been converted in one of the recent meetings. The Yale News reported on April 29 that many students were making open confession of their sins and returning to God.

A measure of the college’s response to Moody may be seen in the urgent request of a group of students that he hold a campaign strictly for Yale. He told the students that he would come if they got up a petition bearing the signatures of five hundred Yale men. Perhaps to Moody’s surprise the names were obtained in a matter of weeks.

The 1878 revival and Moody’s subsequent visits brought about nothing less than a revolution in the spiritual life of the college. One direct result was the founding of the Christian Social Union in 1879, a student Christian group which in 1881 became the Yale chapter of the YMCA, and in 1886, Dwight Hall. Dwight Hall work included campus Bible studies, campus evangelism, and the construction of rescue missions to reach out to New Haven’s outcast and homeless. The work was largely student conceived, student led, and often, student financed.

Through most of the four decades following Moody’s 1878 visit to New Haven, Yale had the largest YMCA in the country, with as much as two-thirds of its student body taking active part. Year after year, Yale had the largest student delegation to Moody’s Northfield (Massachusetts) college conferences, which centered upon missions. For many students, the love of Christ led beyond Yale to foreign missionary work. The class of 1899 initiated the Yale Foreign Mission, which, decades later, became Yale-in-China. Plaques and memorials all over campus bear witness to Yale lives poured out that others might know salvation in Jesus.

Over a century has passed since Moody first came to New Haven, but God’s work at Yale goes on. The questions Moody asked Yale students to ask themselves remain fresh: “What am I? Where am I? Where am I going?” And what does God (not the world) think of me?

Marena Fisher, Graduate ’92

© 1999 The Yale Standard Committee